If Not Words

A Young Man's Journey Toward Meaning

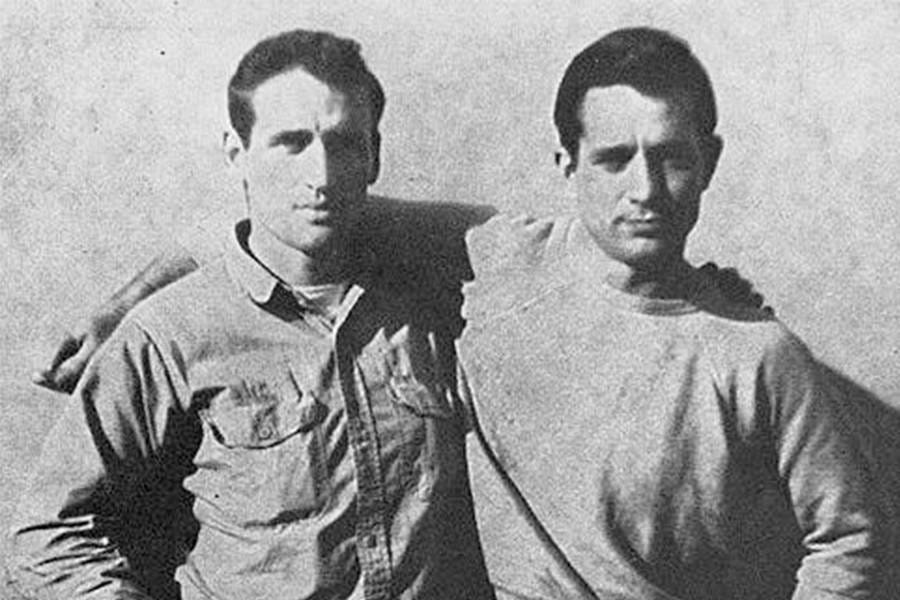

I think of 1978 as my Kerouac period.

Before that was my blustery Hemingway period, and afterward my disastrous Hunter S. Thompson period. But 78 was Kerouac, and in the spring I drifted out of college and began to dream of going on the road.

If Not Words was previously published by the literary journal, Scarlet Leaf Review. (scarletleafreview.com) Estimated reading time: 18 minutes.

Of course, I needed a Neal Cassady—a running buddy like the mad ones that Kerouac famously shambled after, the ones who are “mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”

That’s what I needed. What I had was Pat Kelly.

I first met Pat in Lupoyoma City, a small-minded town next to a big muddy lake three hours north of San Francisco. He was the new kid in eighth grade, from Texas by way of San Jose, with a junkie father in San Quentin and his fortyfiveish mother shuttling drinks at the Weeping Willow Resort & Trailer Court. I won’t go into it here but, at the time, I was in a murky state of social exile myself, due to a local scandal involving my family. What drew me to Pat was our shared status as outsiders, and the fact that he was completely unimpressed by Lupoyoma gossip. That just wasn’t how he measured the world.

I met him because our American History teacher sentenced him to three swats for “cracking wise.” The teacher had a thick wooden paddle drilled with holes to reduce wind resistance. Pat rose from his backrow desk and said, “Now, how much history do you think I can learn from three swats?” He was taller and older than the rest of us. Straight blondish hair, parted down the middle and tucked behind jughandle ears. Tanktop shirt and wide bellbottoms over black motorcycle boots, and his wallet on a silvery chain secured to a belt loop. He took long gangly strides to the front of the classroom, with his chin up and his shoulders back.

The teacher glowered. “Make it five then.”

Pat faced the class and grabbed his ankles. The teacher swung for the fences. Pat overacted a mockish “Ow!” with every blow, and the teacher tacked on another two swats—to zero effect on Pat’s demeanor. I had a front row desk, and after the final swing Pat straightened up and flashed his wide floppy grin at me, then earnestly advised the teacher to watch the Jack LaLanne show. The whole class laughed, but I laughed first. The teacher pointed at the door and ordered me and Pat to the principal’s office. And on the way out Pat paused at the threshold, looked back across the room and said, “Seven a.m., Channel 3,” with a big wink, and turned out the door.

He had something I hadn’t seen before—an attitude or quality I admired, even coveted, but couldn’t name at first.

In those days I collected baseball cards and words—words I read or heard and wanted to remember or accrue to my character. I had the young idea that words had a way of adding up to a man, and I wanted to choose the right ones. Words that said, listen, and rang the air like silverstruck crystal. I wrote down their definitions in a reporter’s notebook that was spiral bound and narrow, with pages that flipped rather than turned. My father was the editor of the town newspaper and I’d stolen the notebook from his dour, disciplined office. I kept it under my bed in a Keds shoebox with the baseball cards.

Exultation was the word I collected for Pat. Triumphant joy. He measured his world in degrees of exultation though he’d likely never seen the word. It was a way of being in the world that I wanted to understand and claim for myself. Late on a school night, with the rest of the house quiet and dark, I sat crosslegged on my bed with the paperback dictionary splayed open in a circle of lamplight and copied the definition into the reporter’s notebook.

We ran together all that school year, in creeks and alleys and neglected vacant lots, in parks and ballfields and quarter arcades. Cut classes to fish by the sunny lake, trespassed in empty dilapidated houses and burglarized the Little League snackshack. Partners in boyish crime.

Once, we kind of stole a car. Just a daytime joyride around the pockmarked backstreets of Lupoyoma in a big Chevy station wagon that belonged to some girl’s mom. That girl would do anything for Pat. And if she didn’t, another girl would. But her mom did not feel the same, and neither did the city police. Their entire fleet of vehicles—all three—converged on the station wagon at a four-way intersection. Black and white Fords and spinning red lights to our left, right, and rear. The street in front of us was clear—Pat could’ve gunned it and started a chase, but he calmly pulled over, put the car in park and turned off the engine.

“Oh shit, we’re going to jail,” I said. “My dad’s gonna kill me.”

Pat grinned and shrugged, “Win some, lose some, partner.”

Between us on the green vinyl bench seat, the girl was sobbing. Pat put his arm around her, gently tilted her head and kissed the top of it.“Don’t worry darlin,” he said, in that Texifornia drawl. Then he opened the car door and stepped out like a fifteen-year-old man.

The girl and I were immediately cast by the presiding adults as good kids under a bad influence, and we were ordered out of the way as officers handcuffed Pat and marched him toward one of the police cars—chin up and shoulders back.

I heard around town that he was sent to the notorious Bottlerock Ranch, the closest thing to reform school in Lupoyoma County. I didn’t see him until a year later, the day we became cousins. Well, my cousin married his cousin, and Pat figured that made me and him cousins too. I still don’t know if that’s correct, but such technicalities were not Pat’s concern.

From that day on, whenever I ran into him, whenever he spotted me in a crowd—at family weddings or funerals, July picnics, or drunken teen parties—he’d always wave his arms and holler out, “Cousin! How the hell are ya!” He never lost that thing I was trying to pin words on, even with the cops always on his case and rarely more than ten bucks and a wink to his name.

I graduated from Lupoyoma High in 75, but Pat already had his G.E.D. and loved to remind me that he earned it at continuation high solely by reading through their collection of Louis Lamour. When I told him I was going away to college, he pshawed and said, “Cousin, you’re doin it the hard way.”

Emmalita Romero was somehow immune to Pat Kelly’s charms. In 1978, she and I were scholarship kids, chasing upward mobility at the small, ivy-aspiring University of the Pacific in Stockton. We had met in Economics 101, which Emmalita eventually aced and I did not complete. We lived off-campus in a rickety one bedroom apartment on a dead-end street—and in sin, as her father regularly assured us.

One February twilight Pat showed up like a long-lost one-man surprise party.

Screeched and skidded to the curb in a dusty copper Lincoln borrowed from his mom’s latest boyfriend. Early sixties Continental with suicide doors, low to the ground and half a block long. He honked “shave and a haircut—two bits,” leapt out of the car, raced around to the passenger side and made a great show of mock chivalry holding the door for a young bleachblonde who emerged waving a fifth of gold tequila above her head. Emmalita and I stood on the brick front steps, both shaking our heads, only one of us smiling. Pat turned to me, opened his arms wide and cried out, “Cousin! How the hell are ya!”

Emmalita muttered something in Spanish and rolled her eyes in my direction.

I gave her a palms-up shrug.

We all got tremendously drunk shooting tequila at the second-hand kitchen table with the blue paint peeling off and the raw wood starting to show. Pat and I took turns telling tales of our juvenile exploits as if they were Homeric epics. Needling each other and arguing over details until we ended up out front on the community lawn in a clumsy, laughable wrestling match.

“Boys.” Emmalita said.

The blonde turned out to be Pi-Delta-something. Pat had sugartalked her right off the steps of the sorority house, and at some point he slipped her out the back door and was balling her from behind, right on our little porch, bent over the wooden railing with a panoramic view of the parking lot—the February cold be damned.

It was Emmalita who opened the door and discovered them, yanked it shut in a hurry. “What the hell!” she said. “He’s fucking her on the back porch!”

I tried a smile. “We did it there once, remember?” Slid my arms around her waist.

“It’s our porch!” she said, slamming me in the chest with both hands.

Emmalita stomped off to bed, the Pi-Delta blonde passed out on the couch, and Pat and I stayed up and finished off the tequila. The blurry dawn caught us still at the kitchen table, commiserating and confessing. Or was that just me? I vaguely remember reading outloud from On the Road and resolutely proclaiming, “I’m sick of teachers you have to call Doctor. They act like they can write a prescription for your whole fucking future. Here, kid, take two Aristotles and call me in the morning.”

“Ya worry too much,” Pat said. “Always did. Come look me up in Santa Barb this summer. Gonna get me a landscaping job, probably get you one too. Gonna build rock walls for rich ladies whose husbands ain’t home.” He shot me a wink and chuckle.

“Yeah, right,” I said. But the possibility took up residence in my mind and hibernated there the rest of the winter.

When spring came around I received a postcard advertising a bar and restaurant called The Palms, in the town of Carpinteria, just down the coast from Santa Barbara. On the front there was a blue-sky picture of a whitewashed building rimmed with green cornices and fronted by a row of towering palm trees. “The Palms” was painted in voluptuous green script arcing high across the white bricks. On the back, the address of the place, the canceled stamp, and in Pat’s half-schooled printing, “The weather is here, wish you were beautiful! Ha!”

I didn’t show the postcard to Emmalita. I tucked it between the pages of my brokenspine paperback of On The Road and reshelved the book in our “library” made of salvaged boards and stolen milk crates.

According to legend, Neal Cassady sent an eighteen-page, sixteen-thousand-word letter to Kerouac which transformed his writing forever. What I got was a nine-word postcard with no return address.

Still, I considered it an invitation of sorts—and a map.

It was late April and late Thursday night, and I had everything except my toothbrush in the new backpack. Two changes of clothes, three harmonicas, two Kerouacs, one Kesey, my old paperback dictionary, two hundred bucks rolled up in a sock, the postcard from Pat, and my reporter’s notebook with room for a few more words. I’d promised myself they would be words of change and becoming, not the cautious preparation of academia.

The backpack was waiting against the wall next to the front door—bright orange nylon, shiny aluminum frame, army surplus mummy bag lashed on, and I told Emmalita, “I want to be on that onramp with my thumb out no later than seven in the morning to catch those business guys headed for San Francisco.”

She’d been in the bathroom almost an hour, showering and getting ready for bed. She came into the living room wearing the white full slip that always knocked me out. Nothing underneath. Long black hair dripping wet. “Baby, it’s a twenty minute walk to the freeway,” she said, “even more with that heavy thing on your back. You can sleep in and I’ll drive you in the vee-dub before I go to class.” She slinked across the carpet and her smile was dressed in red lipstick. She pushed me back on the sofa, pulled off my t-shirt and shorts and straddled me in the white slip.

She shushed me when I opened my mouth to speak—and that was probably a good thing because I might have said I love you.

Emmalita didn’t indulge in that kind of talk. Traditional monogamous relationships were obsolete. She was a liberated Chicana who read Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem and had marched with César Chávez. She dismissed Kerouac as one of the last great chauvinist pigs, but she listened when I read aloud on long car rides and in our bed on hot Stockton nights unfit for sleep or love.

“You get so excited over these words,” she would say, like a new mother saying, “Aw, so cute.” But I would ignore her condescension and talk about the blue echoes of Coltrane’s saxophone in the syncopated rhythms of Kerouac’s prose, and the way it spoke to me that he rejected button-down society to search for his own meaning across the map of America.

When I told my father I was dropping out of school to go on the road, he’d offered me a job at the newspaper.

But when I told Emmalita, she understood. (Of course, I kept Pat Kelly’s name out of it.) We were sitting on the red brick stairs by the front door in the early evening, the bricks still warm from the afternoon heat. We brought out bottles of beer and watched the sun slide into the low skyline across the valley. I showed her the new summer catalog from the university, with the fake snapshots of students at internships, posing with stethoscopes, clipboards and briefcases like children playing dressup. I pointed and jabbed at the pictures and said, “That’s not me. That’s not me. That’s not me either. I’m not in there.”

Emmalita nodded and took a long sip of beer. She didn’t try to talk me out of it or lecture me like a parent. “Go,” she said, still gazing into the distance. “I could never forgive myself if you don’t. Anyway, after graduation I’ll be leaving to law school who knows where.” She picked at the bottle’s label with a fingernail. “We’re young. We each have our own dreams.”

We didn’t want to live our parents’ lives, tangled forever in regret and resentment. We agreed that they were childish, and we thought it a satisfying irony that we were so adult in our acceptance of individual freedom. She even promised to store my records and books—including my stack of rare blues 45s and the first edition Hemingway I’d found at a yard sale.

The day I left, I woke up alone, in the near-dark with the feeling that I was late. I found Emmalita at the kitchen stove frying chorizo and eggs, still in the white slip. She looked at me sweetly over her shoulder. “Your favorite,” she said.

“We don’t have time for breakfast,” I said, but she just turned back to the pan and stirred with the flat wooden spoon. The smell of chorizo rose in steam.

“You know he never found it,” she said. “He drank himself to death. All that going and going and he never found the meaning of anything.”

I sat down at the kitchen table and studied her. So beautiful and smart and surehearted, so luminous of purpose. That was the word I’d written in the notebook, watching her the first day of Econ 101, already pestering the professor with feminist critiques. Luminous. Shedding light. Now I memorized the hair rolling down her back in black waves, her shoulders warmed to gold by the light of the one bare bulb in the ceiling, her shape moving under the slip like a liquid silhouette, the reflection of the lightbulb trembling in her eyes.

I still had to go.

It was eight-forty by the time we got to the freeway, and a rare spring fog had crawled in off the delta. The commuters were long gone and two bums had already taken positions up the onramp. Emmalita pulled over and left the engine running. She gripped the steering wheel and stared straight ahead while I maneuvered my pack out of the back seat. I walked around to her window. She rolled it down and turned her face to me, her eyes wet. I looked at the ground and said, “Thanks for the ride.”

“Will you even miss me?” she said.

“Of course,” I said, and bent down to kiss her.

She reached out the window and slapped me so hard I saw floating spots. “Estúpido cabrón!” she said. “You will miss me. And when you come back, maybe I won’t be here. And if you don’t come back I will scratch all your records and burn your Old Man and The Sea. Pendejo!”

Her rear tires spit gravel as she sped away.

I trudged up the onramp past the two bums so as not to steal first position, which I knew would violate hitchhiker etiquette. At the time I knew that and little else about citizenship of the road. My older stepsister had started me young with daytrips thumbing around Lupoyoma County, but I had never ventured an overnight trip before.

Now I would trace one small piece of Kerouac’s map—if I could ever make it out of Stockton.

The fog was tentacled, the cold insidious. The bum in second position hunkered down on a bedroll in a tattered fatigue jacket. I stood and blew into my cupped hands. The first-position bum watched with gristled detachment. I use the word “bum” because “homeless” wasn’t established as the preferred euphemism in 1978. Drifter sounds too nefarious, hobo too archaic, wanderer too soft-focus. And these appeared to be respectable bums—not recreational or philosophically ambitious, not the dharma bums or wino savants of Kerouac, but respectable nonetheless. When I walked past, each of them offered a chin nod to acknowledge my good manners.

A car or sometimes two at a time came up the onramp every few minutes. It was not a steady stream. I stood shivering, my head bowed, shifting pebbles with the toe of my boot. A car would appear and the two bums and I would present ourselves, one-two-three, in rapid sequence. The bum in the first position wore a blue knit cap and was stooped and gray-stubbled. He held up his right hand as if measuring an inch between his thumb and forefinger to show that he only needed to go a short distance. The bum on the bedroll was younger. He stood up and let his arm hang down with his hand below his hip, his thumb angled out but cooly indifferent. Then me, standing lock-kneed with my arm perpendicular to the road and my eager thumb almost quivering. I made eye contact with every driver, recalling my high school counselor’s interview advice.

A truck stopped and picked up the gray-stubbled bum. He nodded through the window as he rode past. The other bum picked up his bedroll and walked down to the old bum’s spot. He sat down, then looked up and waved me toward him. When I got there he said, “Where ya headed?”

“Santa Barb,” I said, trying to sound suitably traveled. “Actually Carpinteria.”

“Headed down the coast myself,” he said, and he took some time to look me over. I became hotly aware of my new orange pack, my brightly washed overalls and clean farm bureau workboots, my peachfuzz face and the girlish dark hair flowing down to my shoulders. Bangles. Yes, I wore bangles.

The bum said, “Wanna go together?”

I must have looked confused.

“Sometimes it’s better with two guys.”

“Oh.”

“People think it’s easier to be crazy alone.”

“Yeah.”

He put out his hand. “Name’s Terry.”

He wore a red bandana headband over unruly curls of rusty brown hair, and his unfinished beard reminded me of my grandmother’s windowsill cactus. He had dark squinting eyes and a handshake that read like a swim at your own risk sign. He said he’d been on the road for years. Before the army, he’d never been outside Alabama, but he’d come back from Vietnam with a spiteful heroin habit to kick and a desire to see the country. “See what I was killing for,” he said.

Here was a piece of the America I thought I was looking for, the sad and true but unbroken America you couldn’t find in a dorm room or a library stall. Or in a rickety apartment playing house with a future lawyer. Or the dusty office of a podunk newspaper. I now felt that I was officially on the road although I hadn’t managed a single ride. I could see myself on a barstool at The Palms, regaling Pat Kelly with exaggerated tales of my tremendous adventures with Terry the All-American bum.

The sun burned through the fog, then started in on us. Terry had a pair of aviator sunglasses that might’ve been stolen off Douglas MacArthur himself. Dark green lenses and gold wire frames with the looping ear stem. We finally got a ride from a freckled high school kid in a 65 Ford Econoline van. Terry sat shotgun with one elbow out the window, with his windblown hair and red bandana, and the reflections of the traffic speeding across those sunglasses. I climbed in the back and sat on a lumpy mattress covered with a ratty brown bedspread. We rumbled west across the great San Joaquin Valley, straight at the sun.

Late that night, I dipped into the money sock, handed the kid a ten, and Terry convinced him to let us sleep in the van, parked on the street outside his parents’ house in a monochromatic subdivision. But the parents got wise and we were rousted out around dawn, the panicky dad pounding on the side doors until we emerged, then threatening us down the street with a golf club. Nine-iron I think.

That afternoon, we crossed the southern arm of the grayspackled San Francisco Bay on a long low bridge like a highway upon the water. Terry had a Vietnam buddy who owned a bar in San Carlos. The bar was a surly looking place surrounded by chopped and raked Harley Davidsons. Terry marched through the swinging door like no big deal and I fell in warily behind him. Every head in the bar swiveled to stare us down.

Terry’s buddy was a stone outcrop of a man called Sergeant Oliver. Dark straight hair down to his belt, wild thick beard and a big bearish laugh. “You better stick to yourselves,” he said to Terry. “My regulars don’t take to outsiders, and I got no time to save your ass. Again.” The two of them laughed like old times, and Sergeant Oliver confined us to the storeroom with a deck of cards and a bottle of house bourbon.

But, by his own admission, Terry was not a reliable follower of orders. And I was following him. We slipped out when Sergeant Oliver was busy, and Terry made fast friends of the whole crowd by sharing the bourbon and losing at pool. I played harmonica along with Free Bird on the jukebox, and after we helped close up the place Sergeant Oliver locked us in. We slept like ragged children, curled up in the red leather tuck-n-roll booths.

The next day we got sidetracked and stranded in the farming town of Watsonville, where it rained like hell was water. But Terry somehow knew where to hop the fence at the city yard, and we clambered over and sought shelter in huge sections of concrete culvert. There were dozens of these cylinders big as railroad boxcars, laid out in tidy rows waiting for some major construction project. I followed Terry and we ducked into one. Inside it was all cozy echoes, outside nothing but the hiss and patter of rain… until we heard the low snarl of the watchdog. Then it was a cartoon scramble back over the fence and a half-mile jog to an all-night laundromat, where we spent the shivering night soaked through and nodding off in yellow plastic chairs shaped like your butt.

I relished every minute of these complications and travails, and I harbored the furtive belief that some holy chemistry of fate was involved in appointing Terry the All American bum as the patron saint of my road.

In Big Sur, now four days gone from Stockton, we chanced on a woodsy encampment beside the highway, where nearly thirty fellow travelers were set up. This confluence of meandering souls seemed to call for a suitable commemoration. A tiny shack of a store stood across the highway, someone’s weatherbeat hat was passed around camp like a collection plate, and the fire, whiskey and talk burned late into the night. I pulled out a harp and jammed blues with a sunburnt old picker from Show Low, Arizona. Terry met a frizzy haired hippie woman headed up to Mendocino to make pottery, and I believe he spent some time in her sleeping bag. I scribbled the definition of confluence in my notebook. Where two or more streams or paths become one.

I don’t remember lying down to sleep, but I do remember waking up, alone, the contents of my pack dumped on the ground, the money sock stretched out, empty.

There’s plenty of regret and disillusion already built into a hangover without robbery in the bargain.

I never saw Terry again, but I found the aviator sunglasses in a pocket of my backpack—a weak apology I concluded, and I tucked them away in the pouch of my overalls.

Blood-eyed and down to seventeen dollars, I nursed my pride in the woods of Big Sur all day, then slept troubled under a three-quarter moon.

There was a phone booth next to the little store, and in the morning I sat on the nearby lawn and eavesdropped on the desperate phone calls of a few weary travelers. I got to thinking maybe Emmalita would wire me some money back in Monterey. It would mean surrender, but I could catch a Greyhound and drowse in her arms that very evening. I rehearsed the entire call in my head, playing both parts—her finger-wagging satisfaction and my redface shame.

I thought of the postcard from Pat Kelly with the sunlight flashing off the bricks of The Palms. I’d told Terry I had family in Carpinteria who were expecting me. But Pat was not expecting me. I hadn’t seen him but once in the past year. I had nothing to go on but that sunny photo and my own restlessness.

I thought of my father. “A pipe dream,” he had said when I shared my plans. “Son, you won’t learn how to write on the side of the goddamn road.”

“I might learn what to write,” I said.

But my father was an editor, not a writer. To him, words were either essential or expendable, and always in relation to a specific and utilitarian purpose—science, commerce, the news. In his mind, fiction was a toy made of words. He’d scoffed and shook his head. “Might as well stick that thumb up your ass.”

But now I got up off the ground and pulled out the MacArthur sunglasses and put them on like a coat of armor. I strapped on the dusty orange backpack, walked over to the southbound lane and stuck my thumb out for the next car. My hand low against my hip.

Two days further down the coast, I had a ride that would have taken me all the way to Carpinteria, but I got out five miles short in the tiny town of Summerland—because Kerouac had once spent the night on the beach there.

I hunted up a liquor store and spent my last folding money on a half-pint of Southern Comfort and a family-size can of pork and beans. I walked to the beach in the Summerland twilight. I made a driftwood fire, ate the beans out of the can with my pocket knife, and sipped the sweet liquor like sacrament.

There is a certain bliss contained in the moment when one owns a full belly and a full bottle at the same time, even if one also owns an empty wallet. I was bleary and beat and alone without a dollar to dream on, and yet I had the tremendous sense that all was right. In that hour, on that beach, on the map of my heart, I crossed paths with Kerouac.

I thought of that word, tremendous, because it appears so often in On the Road, and in so many contexts that you begin to think he was spraying it around as decoration, unconscious of its specific meaning. I got out the paperback dictionary and read the definition by the firelight: “very great in amount, scale, or intensity.” The root was the Latin word for tremble, and it made me think that Kerouac knew exactly what he was doing, consciously or not. He wanted to suffuse his prose with that deep underlying sensitivity. To bequeath his own shudder at the amount, scale and intensity of America, the world and life. He wanted us to ingest that feeling, swallow it, absorb it and sweat it out the way he had, if only for one night on one beach.

I copied the definition of tremendous onto the final page of the notebook. I sucked Southern Comfort and spoke stumbling poetry to the darkening sky—for the writing gods and for Kerouac, for the full moon, for hope, for words. I stripped to my paisley boxers and danced a silly jig around the fire, and I raised my bottle in a toast to Pat Kelly. Months before, in that drunken dawn at the kitchen table, I was reading from On the Road and he stopped me when I said, “they danced down the streets like dingledodies.”

He laughed and shook his head and pounded the table. He said, “Cousin, what in the holy blue fuck is a dingledodie?”

I tried to explain that Kerouac invented the word. I said, “you have to get the meaning from the story and the rhythm and the way the word sounds in your heart.”

There was a pause during which Pat carefully refilled my shot glass with tequila. Then he stood up and stretched his upper body across the table so he was leaning on his elbows and his face was close and out of focus.

He said, “What I want to know is, do you say more with all these words, or just talk more?”

Now I toasted him from the sands of Summerland—and I toasted my father and Emmalita and Kerouac and Terry the All American bum. Because words do make men. And women and toys and news and futures and lovers and wars, every question, every answer, the whole damn thing including the part we name our soul—the part that’s invisible to our physical senses yet we feel it tremble at life. In the end what is the trembling made of, if not words?

I found my overalls rumpled on the sand. Slipped out the postcard and looked at it with the firelight bouncing off the glossy photo. I turned it over and laughed at Pat’s corny joke one more time, then I tossed it into the flames and watched it catch fire. I pulled Terry’s sunglasses out and threw them in as well. I ran to the backpack and grabbed my notebook. Page after page, word after word, I tore out and crumpled, and I offered them all to the giddy flames.

I slept straight through to the late morning sun like a man sated by exhaustion. I got up and walked into the ocean. All the sweat and dirt and doubt of the road rafted away on the foam. I finally caught a ride into Carpinteria that afternoon, Friday, a full week after I tromped up that first onramp in the fog of Stockton.

I found The Palms, and I found Pat there in a cramped little bar off the restaurant. Maybe six stools at the counter and a few tables in the corner, every spot filled with drinking, shouting, haranguing men. It was a workingman’s bar. They were carpenters, painters, bricklayers and plumbers, and there was not a suit among them or a doubtful word.

Down the bar there was some kind of contest taking place and a huddle of men chanted and slammed their fists on the bar in unison. Of course Pat was in the middle of the commotion. I fished the last coins out of my pocket, ordered a draft and watched him in the barback mirror.

He’d changed somehow. He was shirtless, that wasn’t new. And he sat at the bar like a rooster, still chin up and shoulders back. But the hat was new—a dented straw cowboy hat the color of September hills, the brim rolled up a little on the sides, dirt blonde pony tail hanging out in the back. And the mustache was new—a trimmed biker-style fu manchu that added a thousand miles to his face. But he hadn’t changed that much. The matronly woman who brought my beer told me he was eating raw cayenne peppers on a bet, with two more to go before winning the pile of money laid out in front of him. “Boys.” she said, and shook her head.

Pat drained his mug in one swig and wiped his mouth with the back of a sun-dark arm. He looked down at the waxy red peppers in the clear glass snack bowl. He drew a deep breath and raised his right hand to the edge of the bowl. Then he spotted me in the mirror.

“Well, I’ll be damned!” he hollered out, and he turned on his stool with a holy goof grin and stood up and cried out to the whole bar, “It’s my little cousin!” He made it sound like an extra payday, and some of the men belly-laughed and cheered and lifted their drinks. He held up a finger that said just a second, turned back to the bar and picked up both of the remaining peppers. He held them up for all to see and the crowd roared approval. Then he dropped the red peppers daintily into his upturned mouth.

His shoulders tensed. He worked his jaw. His forehead beaded sweat. His eyes bulged and watered and his open hand pounded the bar. He chewed and swallowed and gagged so his cheeks filled up like Dizzy Gillespie trumpeting high C. He gulped down someone else’s beer and then bowed his head in concentration—or possibly a sinner’s prayer. The crowd hushed. He raised his head, swept up all the money with one hand, punched at heaven and hollered, “Bartender! Drinks all around!” A tremendous cheer erupted like the end of a long bloody war.

I shouted and roared and drank deeply. I exulted.