The Blues & Billie Armstrong 11

A ROARING QUIET

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

Later that winter, I rode my bike out there on a cold sunny day and saw the red car shining and lonely in the circular driveway as I pedaled by. I wondered if the same guy would ever come back to Lupoyoma to cruise Main Street.

Being a thirteen-year-old boy is developmental limbo.

I was no longer wholeheartedly the rambunctious All-American kid running the streets and fields, exploring creekbeds, hopping fences, collecting comic books, ignoring girls. But I wasn’t yet a full-fledged teenager, dating cheerleaders, cruising the main drag, popping zits in the mirror and spiking the punch at school dances.

At thirteen, you’re in the Junior High boys room literally counting the hairs on your upper lip, or in your armpit or your crotch. You get bullied by fourteen-year-olds and you bully twelve-year-olds. You masturbate habitually, reflexively, often without conscious lust or fantasy, simply as a release of surplus hormonal energy. Your dick might suddenly spring hard just from the way the fabric of your underwear brushes up against it when you sit down at your desk. Then the teacher calls on you, and you’re stuck there with your painful little boner as you try to read the Gettysburg Address aloud.

All this flourishing weirdness is turned up to an even higher volume if your mother has recently been featured in the local obituary column. Being an eighth grader with a dead mother in the newspaper is like having cancer. Nobody knows what to say but they’re all sure they have to say something. So they mutter rote clichés about God’s will and faith as strength and time as healer.

One girl came up to me after art class, a girl named Robyn who I didn’t know well. She had long brown hair down to her waist and all her drawings were of horses. She wore a plaid jumper in the colors of autumn and the concerned expression of a girl who has spent far too much time mothering her dolls. “God must have loved your mother very much to take her so young,” she said. “He couldn’t wait to have her with him in heaven.” I knocked her into a bank of lockers with a huge shove and spent the afternoon in the principal’s office.

As the winter deepened a gray and cold numbness came upon me, with the heavy rains and the dark empty days and nights.

Grandma Junia still came by the house most evenings and sat in the living room with my father, fretting over the many ways he wasn’t taking care of himself—working too hard, not eating properly, drinking too much, skipping church, arguing with Cronkite about Nixon and the war. She brought Tupperware containers of food, and she still devoted time to lecturing me on the dire consequences of a misspent youth. “Think of your future, young man. Do you want to spend your whole life in the pig room?”

My father drank Seagram’s 7 and watched TV in the evenings with the curtains drawn and the lights low. “Casserole in the fridge if you’re hungry,” he’d say, without taking his eyes off the news. “TV dinners in the freezer.”

After the funeral, he never once mentioned my mother. Pictures of her vanished from the walls. The flowers she grew in pots on the front porch wilted and were thrown out with the trash. “He’s a grown man,” Grandma Junia said. “Men don’t have time to dwell on these things. They have jobs and responsibilities and they just have to get on with the business of life.”

I took solace in the solitude of these months. I listened to the transistor radio I’d received that Christmas. Before she died, my mother had put it on layaway for five dollars a month at the Sprouse-Rietz variety store. Aunt Laurette paid the last five dollars out of her own pocket and wrapped it up in the San Francisco Sentinel Sports Section with a gift tag that said, To Archer, From Mom.

It was big as a hardbound dictionary and had AM and FM, a telescopic antenna and an earpiece for private listening. I listened to Warriors basketball on KSFO and top-forty hits on KFRC. On New Year’s Eve they counted down the top one hundred songs of 1969, and I stayed up till midnight, alone in my room, to hear the number one song announced—Sugar, Sugar by the Archies. I hated it, based on their name alone. And I couldn’t hear anything in that song—or any one of those hundred songs—that grabbed me by the heart like Sad Hours on the old Grundig hi-fi.

With Hank gone off to basic training, the occupation of printer’s devil ceased to be a new and entertaining distraction. I thought about the dayroom more and more, and Little Walter Jacobs and the scratching sound coming from the hi-fi.

Several times I slid the Keds shoebox out from under my bed, opened it and looked at the envelope I’d found in the pocket of my mother’s dress. I held it and turned it in my hands and examined its details—the blue ink handwriting, the slightly frayed edges, a finger smudge of dirt in one corner. And the weird indecipherable address to PFC J.R. Cole, a string of numbers after the name, then a string of abbreviations, Co B, 1st Bn, 5th Inf / 2nd Brig, 25th Inf Div / APO San Francisco, Ca. And my mother’s maiden name, Evelyn Medina, over a return address on Rawson Road in Two Lakes, a tiny outpost of a town fifteen or twenty miles away from our home in Lupoyoma City.

I was afraid to open it. The pink lipstick kiss on the back flap was like the flattened palm at the end of a crossing guard’s arm. Do not proceed. I realized there would be no peace for me inside that envelope, and I sensed there would be a price for its contents. A trade would have to be made—some truth gained, some faith lost. I wasn’t sure I wanted to pay up. Perhaps Grandma Junia was right: a man must simply move on.

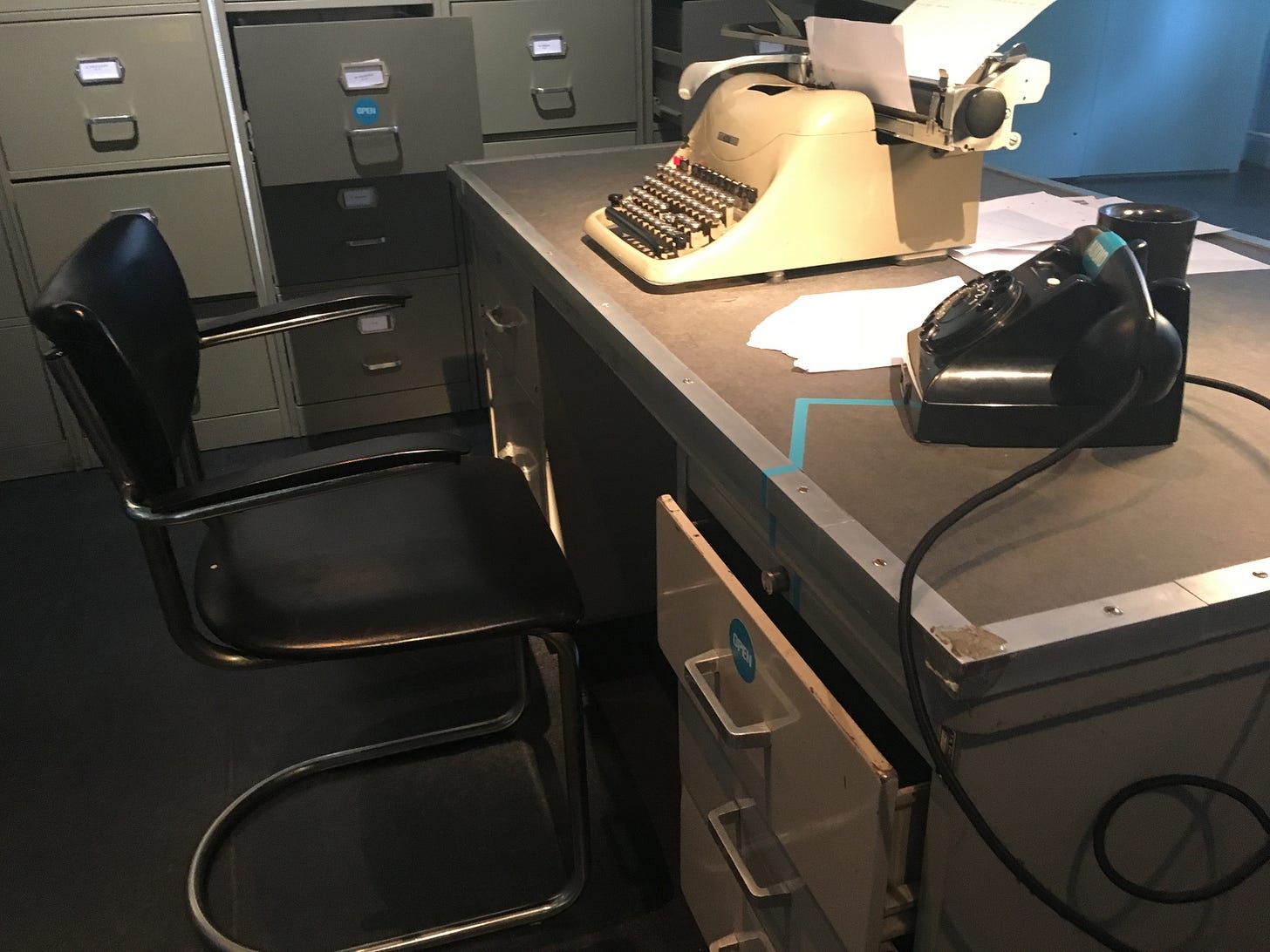

I went to work three days a week. On Saturdays I was alone in the building. Once, I sat in my father’s office, across from his steel tanker of a desk, in the gray chair with the green leather cushion, and I thought about the few times I’d visited him there in the past, stopping by on my way home from school to share a report card, pester a couple bucks or secure his signature on a field trip permission slip.

I imagined he was sitting behind his desk as usual, and I talked to him. I asked if he remembered that time we played catch in the backyard until it was too dark. Or the time he took me fishing up Bottlerock Creek and we each caught a trout and cooked them on a low dancing fire. I asked him why my mother had died. But he wasn’t there to answer my questions.

Tuesdays and Fridays were deadline days, and I would rush straight to the Call & Record after school to help get the paper out the door by six o’clock. My job was to hand-stuff the B section into the A section.

You stand at a wooden counter that is approximately chest-high. The A sections kachunk off the folder at the end of the press, the sound is deafening yet enveloping. You unconsciously attune your movements to the pounding rhythm of the thing, the vibration permeates the concrete floor and thrums in your limbs. You set up two stacks of papers on the counter—A sections on the left, B sections on the right.

You open the top A section with your left hand, slide your thumb inside and widen the opening while your right hand picks up a B section and quickly slaps it into its mate. Your left hand immediately moves the finished newspaper to its own stack on the farther left. Turns of ten, stacks of a hundred.

You do this two or three hours at a stretch, two days a week, all winter long—you get incredibly fast and efficient at this discrete set of precise movements, you become a human machine for those hours. There is a kind of peace in that, a welcome numbness, a roaring quiet.

On Saturdays I was alone in the building. Once, I sat in my father’s office, across from his steel tanker of a desk, in the gray chair with the green leather cushion, and I thought about the few times I’d visited him there in the past, stopping by on my way home from school to share a report card, pester a couple bucks or secure his signature on a field trip permission slip. I imagined he was sitting behind his desk as usual, and I talked to him. I asked if he remembered that time we played catch in the backyard until it was too dark. Or the time he took me fishing up Bottlerock Creek and we each caught a trout and cooked them on a low dancing fire. I asked him why my mother had died. But he wasn’t there to answer my questions.

I was paid twenty dollars a week, cash under the table. The arrangement wasn’t strictly legal, but these things were not so actively policed in those days. Fridays were paydays, and Friday nights in the Lupoyoma winter usually meant deciding between a movie at the showhouse, or a basketball game at the high school. Not much else to do, especially without a car. Or a mother. I saved most of the money. I spent some here and there, at the Weeping Willow game room or the roller rink. I bought a model kit at the hobby shop, a 65 Mustang like Hank’s. I paid for Timmy and Joey and the giant box of Good & Plenty when we went to see John Wayne in True Grit. But it seemed to me there was nothing I could buy that had any lasting value.

On a late March school day when I was home alone, sick with a cold, I finally gathered the courage to revisit the dayroom. My hand trembled slightly as I turned the knob and opened the door. I had to suck in a breath like I was preparing to dive under water. Of course, at some point the room had been straightened. The nightstand lamp turned off. The vodka bottle, the pills, the ashtray full of pink lipstick cigarette butts all removed. The chenille bedspread tightly tucked and flattened.

It was late morning with little chance of my father coming home, but I felt anxious that I might be discovered. The hi-fi scratching sound started up in my head again. I quickly opened the sliding doors on the Grundig’s cabinet. I pulled out the turntable drawer and saw the stack of records was still there, undisturbed. I lifted the entire stack off the spindle and counted thirteen records, a baker’s dozen as my mother liked to say. Some part of me wanted to recover them as relics of history like the bones Dr. Leakey lifted from the ground, artifacts of truth. And something else in me wanted to keep them hidden like pages torn from a diary.

I closed up the cabinet again, shut the door on my way out, and I took the records to my room and stashed them in the bottom drawer of my dresser under two ugly sweaters Grandma Junia had given me over the years, neither of which I’d ever worn.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved