The Blues & Billie Armstrong 15

THE OLD HIDDEN BALL TRICK

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

It is the only picture ever taken of the four of us together—this hasty lineup of cardboard cutouts posing as a family, glued down next to each other by death and marriage and varnished over with wishes and promises.

Although our uniforms said Call & Record across the chest, we were better known as the Paperboys.

It was one of those nicknames that started as a putdown but eventually became an endearment. Our opponents for the day were the Odd Fellows, which sounds like a nickname but wasn’t. They were the New York Yankees of Lupoyoma Little League.

Our team had never defeated them in the years I’d played. They had big hitters up and down the lineup, and they had the fearsome Craiger Robinson, who threw faster than anyone in the league and was said not to own a smile. Craiger wasn’t that much bigger than the rest of us but anyone could see he was harder, inside and out. Nobody was in a hurry to face Craiger Robinson, at the plate or on the mound.

Needless to say, the Paperboys were not favored to win the game. But it was Opening Day— the sun busting through scraps of cloud, the grass freshly mowed after a long wet winter, the bleachers overflowing, the chalk lines flashing straight and white, the stars and stripes up the flagpole, and every underdog’s dream within reach… at least until the final out.

During warmups I took my position at third base and played catch with Joey Quarterman, our left fielder. Our coach, Calvin Fish, had given him the nickname Joey Two-Bits. Joey wasn’t much of a fielder but always a reliable at-bat, so sometimes the nickname morphed into Joey Two-Hits.

The Paperboys’ starting pitcher for the day was none other than Timmy Bilderback. Timmy was short and skinny but tough as homemade jerky. He wasn’t as strong as Craiger Robinson, but he was scrappy. He hated to lose. Timmy took the mound and loosened up his arm by lobbing throws to the catcher. I threw to Joey Two-Bits and half-watched as the two small stands of wooden bleachers filled up with Lupoyomans exchanging greetings and gossip.

My father sat with Mr. Terwilliger and the salesman Les McGoogan. Darlene sat next to Grandma Junia, and neither of them looked too happy about it. I saw Billie find a spot along the top row, close to Alice Terwilliger, who had replaced my mother as the official scorekeeper for our team.

Percival J. Terwilliger had come to fatherhood somewhat late in life and his daughter Alice, at fifteen years old, was young enough to be his granddaughter. She was a tall, quiet girl with shoulder-length black hair, worn with bangs cut straight across at the eyebrows. She was an A-student who wore glasses and worked in the library after school.

Among my friends Alice was thought irredeemably plain, but I secretly found her alluring in her gawky vulnerability. In any case, Alice was not someone you’d automatically picture as a friend for Billie, but from a distance it seemed they struck up an instant rapport, and I wasn’t sure how I felt about that.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw a flash of color and there was a candy-apple-red Mustang pulling into the parking area beyond left field. I stood at third base with my back turned to the plate and watched a soldier get out of the car. An excited murmur fluttered up from the bleachers as everyone recognized Hank Timmons striding toward us in his impossibly crisp khakis, pressed shirt and polished black boots, the blade of his garrison cap slicing the air.

He looked bigger than I remembered and solid as a closed fist. It seemed like the world stopped. Players, coaches, spectators, vendors, umpires and even the unruly children along the banks of the creek took a moment to register the transformation of the boy they thought they knew so well.

When Hank reached the bleachers, Mr. Terwilliger was the first to stand up and shake his hand, then my father and then Les McGoogan. The women all straightened their spines and smoothed out their clothing, even Darlene and Grandma Junia. A dirty-faced little kid ran up and saluted until Hank returned the gesture. I looked to the top row of the bleachers, where Alice and Billie stole glances at the soldier and leaned toward each other as if hatching a conspiracy.

Coach Fish checked his watch, blew the whistle and called, “Come on in, boys.”

The Odd Fellows started onto the field. I was still standing there watching Hank and the crowd. Craiger Robinson walked by and said, “Get off the field, Archie.” At some point he’d learned that I didn’t like the name, and after that he wouldn’t call me anything else.

I was our leadoff hitter so I hustled into the dugout, grabbed my bat and helmet and walked out to the on-deck circle to watch Craiger warm up. Hank came up on the other side of the chain link fence. He said, “Hey Bullseye, how’s it hangin?”

It gave me a little rush of pride that he bothered, and I hoped Alice and Billie were watching. “Okay,” I said. “How’s the army treating you?”

“Everything’s copacetic,” he said.

I didn’t know what copacetic meant, but it sounded good. I said, “But they’re sending you to Vietnam, aren’t they?”

“Yep, I’m home for a few weeks, then I’m gonna go shoot me some gooks,” he said, and it came out weird, like a cross between funny and mean. He was different and not different. He still had that aura of cocky mischief, but seemed more distant and stiff.

Meanwhile, Craiger Robinson threw his last warmup pitch so hard the catcher yowled and shook off his glove to rub his hand. He didn’t bother to throw down to second.

The umpire pulled his mask down over his face and hollered, “Play ball.”

The game eventually came down to the sixth and final inning, with the outcome still in doubt. In the Paperboys’ half of the sixth, I walked, stole second base and scored on a double by Joey Two-Hits. Now we had a five-four lead as we took the field for the bottom of the sixth.

We were three outs away from an upset victory over our perennial nemesis. Standing at third base I was grinding my teeth with the want of it. It was only the first game of the season but I was seething with a wild sense of impending destiny, even justice. It crossed my mind that the loss of my mother, the remarriage of my father and all the other perceived impositions of my short imperfect life should entitle me to one small dream come true. I thought maybe the universe owed me, and I was ready to collect.

The Odd Fellows were down to their last out when Eugene came to the plate. Eugene was short and round and comically slow, but he could hit the ball a Lupoyoma mile—and he was Craiger Robinson’s little brother.

Two down with the bases empty, Timmy Bilderback on the mound and the Paperboys on the edge of what in our young minds would be a historic upset. Eugene Robinson stepped into the batter’s box and took a ready stance. Ball one, low and outside. Ball two, high and tight.

Coach Fish paced back and forth in the dugout, a half-step behind his beer belly, shouting as us to stay calm. Most of the chatter from the stands faded into white noise, but I could somehow pick out Hank yelling, “Look alive, Bullseye! Look alive!”

Timmy went into his windup. I dropped into my crouch by third base, popping my glove and my wad of Juicy Fruit, chanting with the rest of our team, “Hey-batta-batta-batta-ssswing!”

The ball comes off Eugene’s bat with a reverberating thwack and soars toward left field like it was shot out of one of those old cannons on the courthouse lawn. Over in right field, a rusted chain-link fence backed up against the Weeping Willow Resort & Trailer Court and if you hit one into the trailers it was an automatic home run. But in left field where Eugene’s hit is headed, there’s no fence at all. The grass just thins out into hardpan, then runs into the asphalt parking lot, and when you hit one out there it’s a mad footrace.

Fat Eugene is chugging hard around the bases. Joey Two Bits is chasing down the ball in the outfield dirt. The crowd roars to its feet. Eugene rounds second and barrels my way. Joey snatches up the ball and whirls and heaves a throw. Eugene dives face first and slides into third in a heap at my feet as Joey’s throw bounces once and lands in my glove. The umpire yells, “Safe!” and spreads his arms like airplane wings. Half the crowd cheers and the other half groans in the same breath.

The Odd Fellows third base coach immediately calls timeout and Eugene stands up, covered in dirt from cheeks to shoelaces. He’s sucking air and smiling wildly in a cloud of his own dust like Pig Pen on Charlie Brown. In the crowd, fathers lean forward with elbows on knees, and nervous mothers hold their hands over their mouths the way mothers do.

Craiger Robinson is already standing by the batter’s box taking vicious practice cuts… and smiling. The look on his face instantly clarifies for me who on the field is psychologically best suited to the moment… and who is not. A big hit from Craiger would cost us the game. Fear strangles my chest.

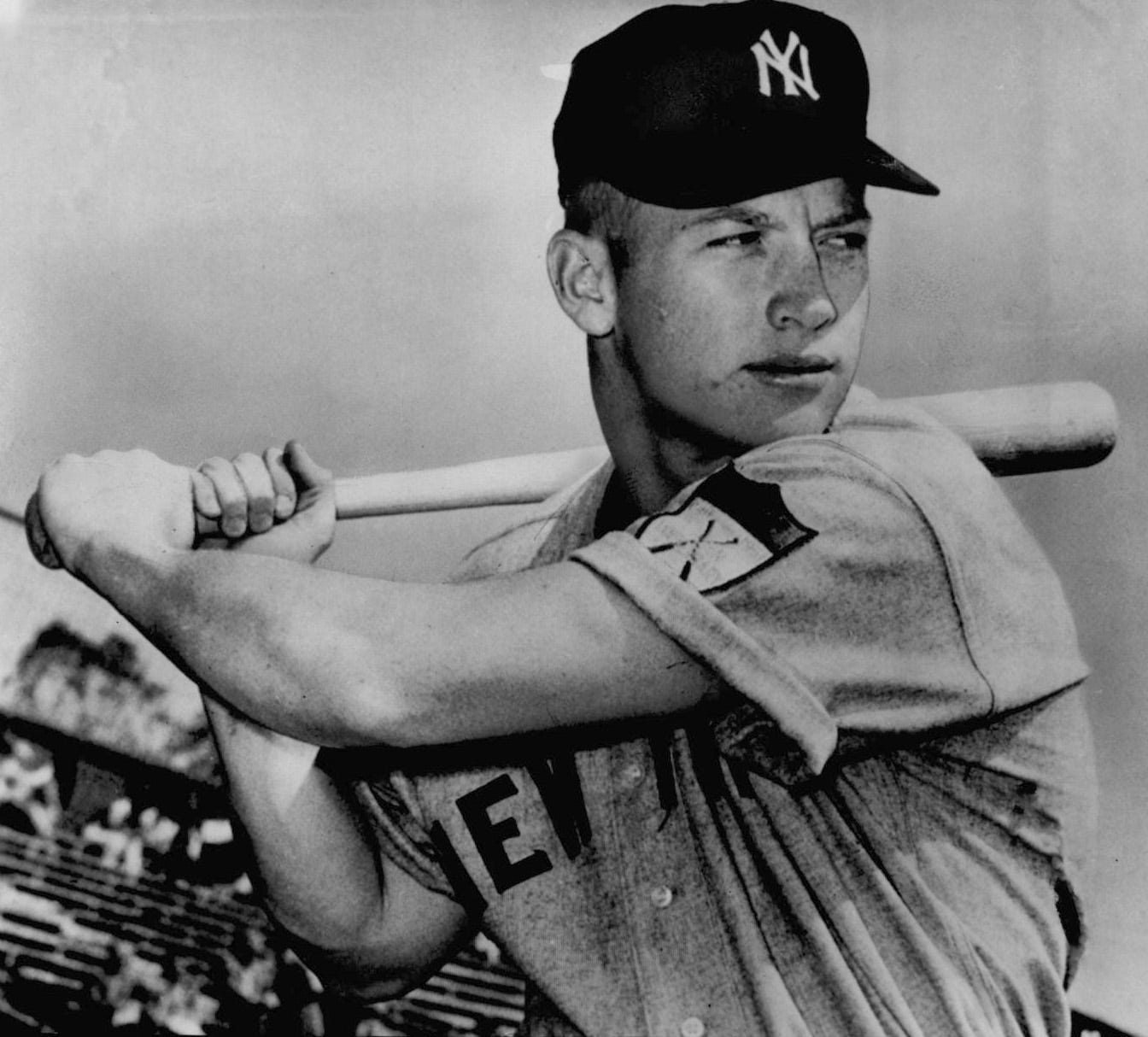

I still have the ball in my mitt so I walk toward the mound and Timmy meets me halfway. He holds out his glove for the ball. I move in close and put the ball in the pocket of his glove. Then I quickly take it out just before he puts his hand in and I slip it back into my own glove. Timmy looks at me and reads my eyes, and we both say it together. “Mickey Mantle.”

Six years before, in the 1964 World Series, Mantle and the New York Yankees met the St. Louis Cardinals.

The Yankees were in the Series practically every year back then—they were the Odd Fellows of Major League Baseball.

The Cardinals managed to win the first game but dropped the next two.

In game four, the Yanks took a three-nothing lead on a single by Mantle. The next Yankee batter blooped a single to center field and Mantle loped into second standing up. The Cards’ center fielder threw the ball in to second baseman Dick Groat, and Groat threw the ball to the pitcher. The pitcher fiddled with the resin bag and toed the rubber. Mickey Mantle took a three-step lead off the bag and, before anybody knew what was happening, Groat ran over and tagged Mantle out.

It was the old hidden ball trick, staple of sandlots and schoolyards. Groat had the ball the whole time! He had faked the throw to the pitcher and made a fool of the great Mickey Mantle of the invincible New York Yankees on the game’s biggest stage. It stunned the fans and it stunned the Yankees. Their bats went cold, and the Cardinals came back to win that game on a grand slam and eventually went on to win the Series.

Timmy Bilderback and I were both seven years old that Sunday in 64. We couldn’t get the game on TV so my father let us listen on the radio in his new Plymouth Fury. He had brought it home only two weeks before, and it was the first brand new car in my life. It was root beer brown and had space-age pushbutton controls in the dashboard.

We each stretched out on the two-tone brown and cream vinyl upholstery, Timmy lying across the back seat, me in the front. We turned up the radio, stared up at the blank, beige headliner, and discovered teleportation. We were part of the first TV generation—we thought a car radio was just Top 40 hits or background noise on a long ride to see relatives. We didn’t yet know entire worlds could be called forth and made to shimmer behind your eyes by the sheer power of Curt Gowdy’s voice. Neither of us ever forgot that day in the Plymouth or that World Series game.

I went back to third base, and Timmy went back to the mound with nothing but his fist in the pocket of his glove.

The ump said, “Play ball!” And when Eugene took two steps off the bag, I hopped over and tagged him with my glove, then held up the ball like a white shining pearl.

Bedlam I believe is the proper word: a scene or state of wild uproar and confusion. Eugene’s fat jaw unhinged. The crowd cheered and groaned and laughed. I heard a man’s voice say, “What the hell?!” The umpire looked back and forth from Timmy’s empty glove to the ball in my glove, back and forth again, then slowly raised his fist and made the out sign.

Eugene stamped his feet in the dirt and yelled, “No fair! No fair!” Frustration welled up in his eyes and he stood with his palms turned up to the sky in supplication to the baseball gods—or any god who might answer. But none did. Hank and the rest of the Paperboys gathered round Timmy and me, shouting and slapping us on the back. Poor Eugene yanked off his batting helmet, crumpled down in the basepath and began to cry.

The fearsome Craiger Robinson stood at home, glaring and pointing at me with his bat in one hand like Babe Ruth’s famous called shot.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved