The Blues & Billie Armstrong 24

A THOUSAND LIVES

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

“Like a meeting of the minds?” I said, because I’d read that phrase somewhere and thought it hinted at something important. “Like a meeting of hearts,” Pop said.

I didn’t think I would ever know a woman that way.

We stood in the dirt, thumbs out, still in silence.

Now that we were back on the highway there were plenty of cars, but they roared by at fifty miles an hour, kicking up gusts of hot air that blew Billie’s hair back from her face. I toed the gravel. Ten minutes passed. Twenty.

“Wanna check the place out?” she said, with a might-as-well nod across the street.

The Bus Stop Antiques & Treasures occupied a repurposed gas station built of dirty white cinderblocks. A collection of rusted gardening equipment decorated the flower beds along the front of the building. The two big picture windows were hand lettered: USED & RARE BOOKS, FURNITURE, GLASSWARE, JEWELRY, SILVER & GOLD, CLOTHING & MORE!

A jumble of sleigh bells and wind chimes rang when I pushed the door open, but no one came running to serve us. Inside, dust floated in the sunlight slanting through the windows. Overcrowded shelves sagged with colored glassware, delicate figurines of Japanese fishermen, old cameras, old radios, odd collections of salt and pepper shakers and engraved Zippo lighters and little spoons from historic monuments and faraway states. Stacks of books clogged the aisles, straight-back chairs dangled from overhead beams, crooked paintings lined the walls. Against one side wall, racks and tables overflowed with clothing and the smell of musty cloth and leather hung in the air.

Billie headed straight for the wall of clothes. I stood where I was, next to a small counter that doubled as a glass display case for jewelry and old coins and stamps. A huge antique National cash register sat on the counter and towered over me. It was one of those big brass things that looked heavy enough to anchor a ship. I called out to Billie. “Hey, I wonder if they have any old blues records here.”

“Blues records?” said the cash register. Or so I thought. Behind the counter stood a tiny old woman with a gray afro. She couldn’t have been much more than four-and-a-half feet tall, shorter than my grandmother Molly. “What’s a little white boy like you want with the blues?” She wore dungarees like a sailor and a green grocer’s apron and stood with the poise of a dancer or maybe a judo expert.

“Wow, I love your store,” Billie said, suddenly standing next to me, smiling. “It’s like the world’s biggest closet—full of a thousand lives.”

“Well, maybe not a thousand, but I’ll take that as a compliment,” the woman said.

“I’m Billie.” She stuck her hand over the counter.

The woman shook Billie’s hand and said, “Frankie.” Next thing I knew, they walked and talked right past me, arm in arm, and left me standing at the counter while Frankie gave Billie the grand tour of the premises.

I found some bins of used records against the back wall. Mostly old-people music like Liberace and Lawrence Welk and Mitch Miller. I’d want to get rid of that stuff too—so manufactured and prissy. I didn’t know much about the blues yet, but I knew it was the opposite of that.

Billie flitted around the other side of the room, pulling clothes off the table and the racks and holding them up against her body in front of a cracked full length mirror. Frankie followed her around asking her blouse, bust, hips and dress size and handing her things to try.

Billie struck different poses and made faces to go with each article of clothing. Then she started the impersonations. She scurried around with a yellow dress and a feather duster, and in her mother’s voice she said, “Oh Billie, you have your whole life ahead of you, don’t waste it arguing with the world.” She grabbed an old pair of eyeglasses from a shelf, put them on and took them off, rubbed the bridge of her nose and wrinkled her brow like my father in pained thought. She stood rigid behind a 1940s style jacket with padded shoulders and did a dead-on Grandma Junia, “You’ll never go far with that attitude, young lady.”

I laughed and laughed, and Billie turned and turned around the room like a little girl at play. Frankie said, “Where you kids from anyway?” with a hint of admiration. When I said Lupoyoma City, she looked at Billie, shook her head and said, “She ain’t from Lupoyoma City.”

Then Billie did Hank Timmons with an army uniform and a sideways garrison cap. She marched in circles. “Which way is Vietnam, Bullseye?” But she stopped and laid the cap back on the display table. She held the uniform up to her body and gave me a serious stare, “Man, I hope you never have to wear one of these.”

“Oh this motherfucking war,” Frankie said, with a look like she’d surprised herself by saying it out loud.

“Aw, look at this!” Billie said, right back to digging among the clothes. “Archer, come here.” She held up a suit. Even on the hanger it was sharp and trim looking—medium gray, with a four-button vest and creased slacks. I walked over and stood stiffly while she took the jacket off the hanger and held it up to my back. Then the pants, along the side of my leg.

Frankie nodded at the fit.

I checked the price tag and winced. Billie held out her hand and I put all my money in it—two wadded up dollars and some change. She took the suit to the counter and dug in the pockets of her overalls to make up the difference. “You can pay me back,” she said. She’d previously teased me about the Dodger blue suit in the wedding pictures and seen my embarrassment. Maybe she understood I couldn’t be thirteen in that suit.

Frankie rang the sale up on the big cash register and put the suit in a paper bag. “You never answered my question, young man,” she said. “Why you looking for the blues?”

I shrugged. “Seems more real than a lot of other stuff these days.”

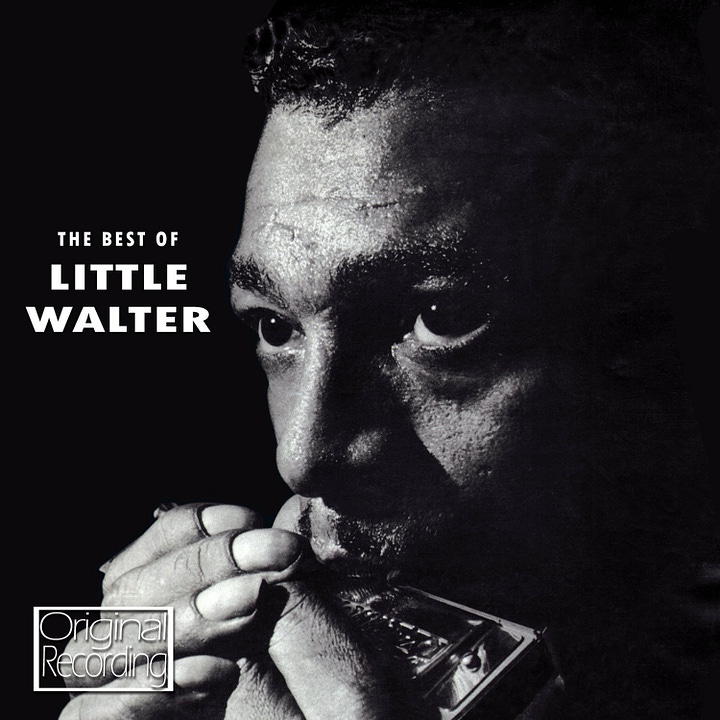

Frankie gave me a doubtful look, but then smiled. She held up a hand that said wait right there, and she disappeared through a door I hadn’t noticed before. She came back with a small stack of albums across her arms and plopped them down on the counter in front of me. Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, a few others.

She said, “these were my husband’s,” and pointed out a framed photograph on a shelf behind the counter, a young Black man in military uniform with determined eyes and a proud chest. “I had them out for a couple years but they didn’t sell. You take them. On the house. They deserve fresh ears.”

“Did he die in Vietnam or something?” I said, thinking of her earlier curse against the war.

But Frankie said, “No. Plain old heart attack. Been sixteen years now.”

I thanked her as she bagged everything up. Billie gave her a hug, which I thought was extravagant but Frankie clearly welcomed the gesture—the two of them had some instant connection I didn’t get.

We went out the door and stood again in the blonde dirt by the side of the highway. Billie faced the traffic with her thumb out, and I watched the wind from a big truck blow her red hair back to reveal that magnificent defiance on her profile.

“You could be an artist here,” I said. “The parents said you’re free to leave when you turn eighteen, but you don’t have to. You could change your mind.”

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved