The Blues & Billie Armstrong 26

LITTLE GREEN ARMY MEN

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

I said, “You heard what Laurette said about Frankie, right? We didn’t realize who we were talking to. We gotta go back and talk to her soon as we can.”

“Absolutely,” Billie said.

Five o’clock came and went, but Billie wasn’t home yet.

Darlene Beverly was in the kitchen, cooking something I would soon be expected to eat and praise. Her cooking always smelled like hamburger in a frying pan—I swear, the woman put hamburger in everything.

My father was reclined in his chair, watching the news, wrinkled white shirt and loosened tie with a highball in hand and a Camel burning in his mouth.

“Do you know where your sister is?” My father said, when I came out to check on dinner.

Darlene stood in the archway between the kitchen and living room, eyeing me and drying her hands on a dishtowel. She had a new hairdo, a poofed-out flip so petrified with hairspray that it shook like Jello with the movement of her hands.

“Stepsister,” I said. “She went to the library.”

My father nodded, took a sip of his drink. “When she gets home we’ll have a talk.”

Instant paranoia. Maybe Laurette had ratted us out after all—for cutting school and hitchhiking out to Rawson Road. We’ll have a talk was certainly prologue to I’m disappointed, followed shortly by you’re grounded.

But it didn’t happen that way.

An hour after dinner, Billie blustered through the screen door. She carried a folded newspaper under her arm and charged through the living room so quickly no one got a word out until she was no longer in the room.

“Billie?” Darlene called after her.

“I want to speak with you, young lady,” my father tried to command her presence.

Darlene rose from the flowered sofa. “I’ll just go see if she’s okay.”

I waited a few beats, then followed down the hallway at a distance that, at least in my imagination, allowed me to appear only casually intrigued.

Darlene stood at the doorway to the room formerly known as the dayroom. “Billie, what are you doing?” I heard shaky confusion in her voice.

“I’m leaving,” Billie said.

I gave up my pretense of equanimity and edged up to a rubber-necking position behind Darlene. Billie was dragging her duffle bag around the room with one hand, and with the other hand yanking clothing from open drawers, gathering art supplies from the vanity, grabbing paperbacks off the nightstand, and cramming it all into the duffle.

“You just got here,” Darlene said and laughed her nervous laugh as if she didn’t quite understand, as if she thought Billie was packing all her belongings to go out to a Lupoyoma house party for the night.

“I need to make some phone calls,” Billie said. “And I’ll need a bus ticket. Or maybe I should just leave now and hitchhike to Akron.”

“Wait, wait, wait.” Darlene flung her hands up in dismay. “What on Earth are you talking about?”

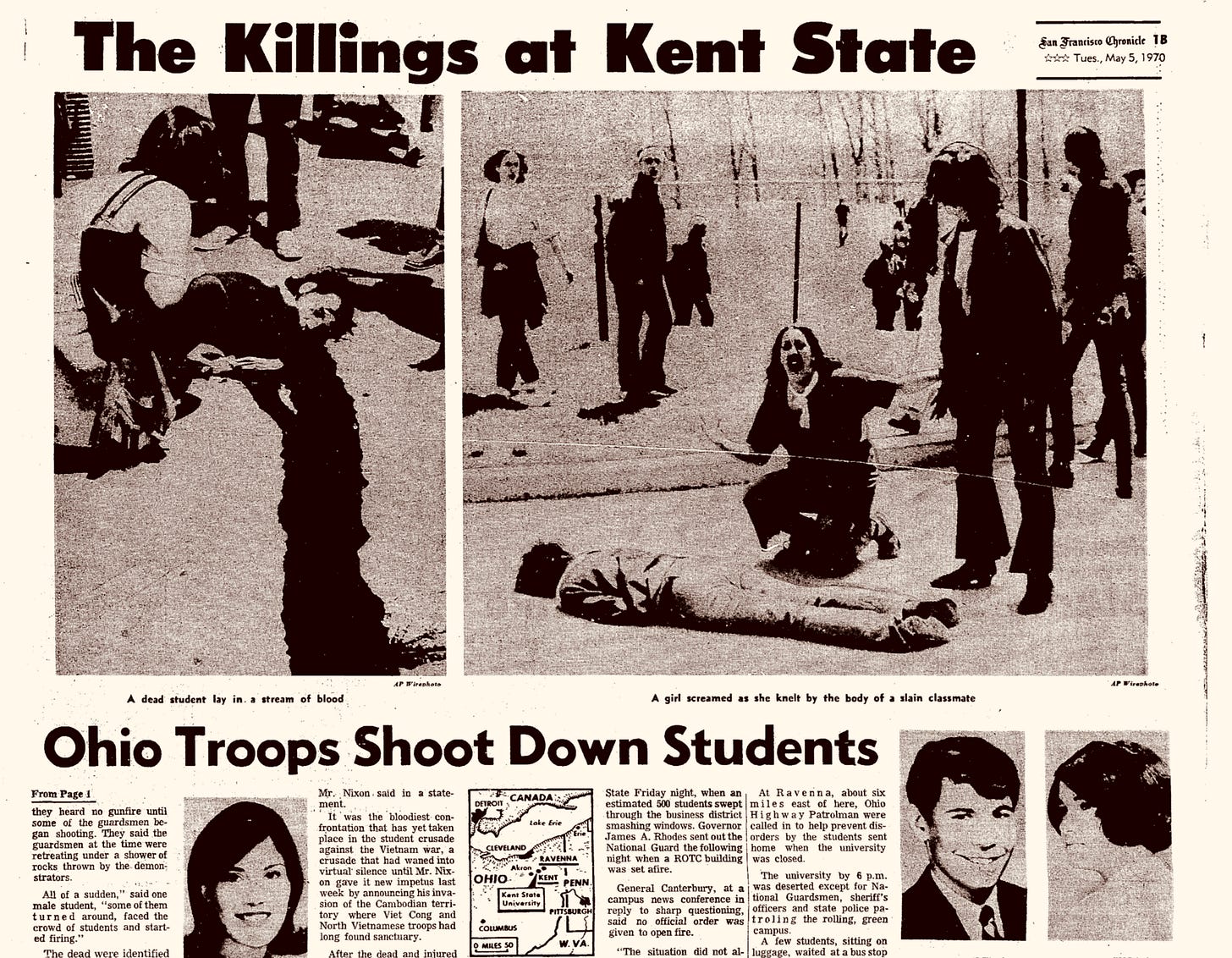

Billie picked up the newspaper that now lay on the chenille bedspread. She snap-tossed it like a Frisbee and some pages spun out around the room, but the front section hit Darlene in the chest and fell to the floor. She scooped it up and held the paper out in front of her. I craned my neck up and down, right and left and around her inflated hair and saw it was the San Francisco Sentinel, evening edition. Then I caught the huge headline above the fold: Four Kent State Students Dead as Troops Open Fire.

“The government is killing my friends.” Billie said.

“Oh my God,” Darlene said, scanning the page, slack-jawed.

“What the devil is going on here?” My father came up from behind and pushed past me and Darlene and into the room.

“Oh my God,” Darlene said again, her face shock-white as she passed the paper to my father.

“Yes, yes, I know. This is why I wanted to talk to you, Billie,” he said. “Now, I don’t want you to over-react. There’s no reason to get emotional. And no reason for you to get involved.”

I remained in the doorway, suddenly feeling all the tension in the room like the audience at a Lupoyoma High School production of some Arthur Miller drama. Darlene and my father hit their marks over by the art-deco vanity. Billie sat center stage on the edge of the rollaway bed, still in her cutoff overalls and the work boots with red shoelaces. The duffle bag stood upright, leaning against the bed.

“I know people there!” Billie said. I’m sure my father saw the clenched anger on her face. “I was living right across the street a few weeks ago,” she said. “Now four kids are dead, eleven wounded. Man, I never thought the fucking pigs would just shoot us down.”

“That kind of talk will not fly around here, young lady.” My father shook his head, grimly, resolutely, still examining the Sentinel front page. “These people are criminals. They’ve been rioting for days. Throwing rocks at the police, setting fire to buildings, shooting at soldiers. Burning flags.”

“No. Nixon and Governor Rhodes are the criminals… and people like you, always going on and on about law and order instead of right and wrong.”

“Now, Billie,” Darlene said, trying to tamp down the energy with a wave of her hand.

But my father was stunned. “I’m a criminal? After getting you out of jail and taking you into my home? I’m the criminal and you and these… hoodlums… are the victims? Is that right? Because I’ll tell you what—I think they should’ve shot more of these ungrateful bastards. Maybe that would teach your whole sorry generation a lesson.”

Billie turned to Darlene. “What is wrong with him!” she said. “I mean, I knew one of those girls, I met her at a party. She wasn’t a hoodlum, she was just a sweet plain-jane who wanted to be a speech therapist. And now she’s dead, and that’s all he has to say?”

“Billie, this is what got you in trouble in the first place,” Darlene said. “All this arguing. It never solves anything. You already ended up in jail once, now you want to get yourself shot?”

“They’re my friends!”

“Billie, please,” Darlene said.

“What do you kids have to protest anyway?” my father said. “You live in the greatest country in the world, you’re wallowing in modern convenience and all this permissiveness. You read a few books and listen to some long-hair bums with guitars and suddenly you think you know better than the President of the United States? You’ve got the whole thing backwards. You need to grow up and see what it’s like to raise a family and contribute to your community. You want to be treated like an adult? Well, adults pay their own way, for your information. And they don’t set fire to their own towns.”

Billie turned back to Darlene, disgust contorting her face. “He thinks buildings and flags are more important than teenage boys dying in the jungle. But I’m the one who has it backwards?”

“Mike, couldn’t you just let her use the phone?” Darlene said, straining for compromise.

But my father simply could not accept Billie’s questioning—much less her complete rejection—of his authority.

“You’re grounded. You’re not going anywhere,” he said. “No bus ticket, no calls. You leave this house tonight and I’ll have the police looking for you. Do you understand? You’ll be back in juvenile hall by morning.”

I’d never seen my father so close to losing his button-down cool. He had rolled up the newspaper and was strangling it in his fist. He rattled it in the air and even raised it once as if he might strike Billie. But the dare on her face, the heat of her green eyes, stopped him mid-air.

“Michael!” Darlene said, startled. And disappointed.

My father slowly set the newspaper down on the dresser.

I quickly stepped into the room and picked up the paper, unfurled it and looked at the front page for myself. The scream on a girl’s face—kneeling over the fallen in terror and shock. Face-down bodies in puddles of shadow. Incomprehensible.

This gunpowder thread of death had been in the news most of my life. JFK, Dr. King, Bobby, My Lai, black body bags and flag-draped caskets moving across the TV screen behind breathless reporters. But this felt different. Allison Krause, 19. Jeffrey Miller, 20. Sandy Lee Scheuer, 20. William Schroeder, 19. The names captioned under their high school yearbook photos.

I crossed the room and sat on the bed. I looked up at my father, hoping for some peacemaking gesture to cut the barbed-wire silence. He said nothing.

“It could’ve been Billie,” I said, and I felt that reality down in the muddy bottom of my belly.

He removed his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose and searched down at the old brown corded rug where as a child I had mustered troops of little green army men.

He shook his head, frowned at the rug, put his glasses on, left the room.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved