The Blues & Billie Armstrong 30

MOTHER'S DAY

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

“Sure enough, a few days later, cops banging on my door.” She waved a hand at the mess around us, the half-empty shop and the swept-up glass and the disarray. She gave it all an arms-wide what-the-hell shrug. “You see how that worked out.”

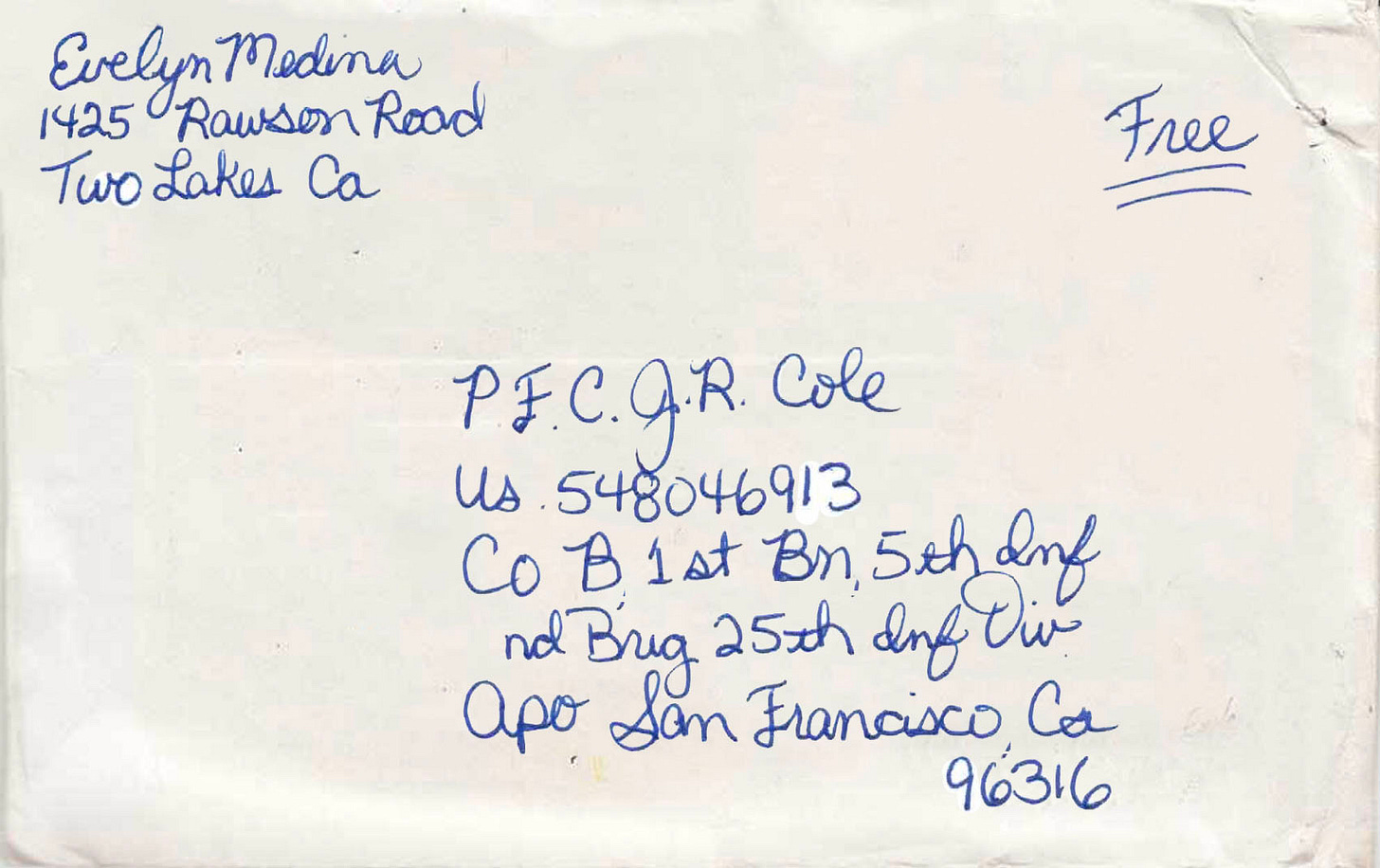

Frankie pushed the envelope across the table and I silently read the address for the hundredth time.

PFC J.R. Cole—all the numbers and abbreviations, Co B, 1st Bn, 5th Inf / 2nd Brig, 25th Inf Div / APO San Francisco. “Do you know happened to him?” I said.

“I got a postcard once—just I’m fine, how you doing, and thanking me for helping with the letters. It was all hush-hush. He sent his letters care-of me, and I’d mail hers over at the Two Lakes post office. She was very careful—always parked her car round back when she came, so no one would see it from the road. And we’d small talk a bit. How’s he doing, I’d say. And she said the war was wearing hard on James, but she didn’t say much more than that. Then the letters stopped coming, and your mother stopped coming, and I never heard another word. Figured James maybe died in the war. Didn’t know about your mama, though.”

I picked up the envelope and slid it back into my shirt. A strange dead-end emptiness hit my stomach—like an elevator dropping too fast. I felt near tears and sickness both.

Frankie seemed to pick up on my emotional state. “Look, son—your mama was a good woman, you hear?” she said. “Whatever’s in that envelope, or those other letters, doesn’t change that. She was a good woman, she just desperately needed something she couldn’t have.”

“Billie says I should try to understand because they were in love.”

‘Well, love is crazy, boy, and that’s a fact. Love is like water in the desert. You thirsty enough, you’ll crawl on your belly for it, even if it’s a mirage.”

I looked around again at the mess her store was in. “Do you regret helping them?”

“Yes and no,” she said. “You gotta stand for something… or you don’t stand for nothing.”

Later, when I was already loaded up in Garfunkel’s passenger seat, Frankie ran out to the parking lot shouting, “Hold on!” She came to the window of the van and handed me a record. It was a 45 in a worn and yellowed plain-paper sleeve. My Heavy Load by Big Mama Thornton. She said, “When James and your mama ran off, this one got left behind somehow, and I remember it was one of her favorites, one of my husband’s too.” I hesitated and she said, “No, you take it. Truth is, I never cared for the blues like he did. And now it just takes me backwards in the worst kind of way.”

Garfunkel pulled the van over at the corner of Main and Fourth streets, ran around and popped the side door, easily lifted my bike out and set it down on the sidewalk in front of me.

He gave me a soul-shake. “Take care, dude,” he said, while our hands were clasped. “Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do.” Which I figured was a pretty short list.

Watching him pull away from the curb I felt a tightness around my heart, another stab of nostalgia for something I’d never actually had. I wanted to know more about my mother and J.R. Cole, and why she did what she did, but the answers I needed still lay beyond my grasp. And maybe it was all a waste of time and worry in the first place. Marriages fall apart, accidents happen, people die, truth is debatable. And men move on. Right?

My father’s Plymouth was not in the driveway or at the curb in front of the house on Fourth Street. I dropped my bike on the weedy lawn and once inside I headed straight for the dayroom and added the Big Mama record to the stack of 45s still on the old Grundig. I switched on the turntable and dropped the needle. I guess I had some pathetic idea that listening to this last record would close the chapter that began with the scratch-scratch sound and Little Walter’s harmonica on that gray Wednesday the year before. You have to understand—this was back when I still believed the past could be left behind.

The music was stripped-down naked, just acoustic slide guitar and Big Mama’s rich and round, tender but tough voice. The guitar steely and slippery with a thumping bass and the whine of the slide stinging like papercuts across the heart. The lyrics forlorn, bruised, weary of the stubbornness of hope, a woman in search of rest and somewhere to let go of the heavy load of her sorrows.

The closet door was half open and for some reason I peeked in. A line of empty wire hangers dangled from the wooden dowel. Billie never hung up anything. The boxes marked for Goodwill were still stacked against the back wall, my mother’s hatbox on top, looking innocent. I opened it and lifted out the navy blue hat and saw my mother laughing, eyes of mischief, riding the carousel at the San Francisco zoo. I thought again of my original plan to set the whole confusion on fire.

I set the hat and the newspaper packing material aside and inventoried the other items: the kaleidoscope, the abalone shell, the motel key, the Kennedy button and the Polaroid of my mother on a windswept bluff above the ocean. I counted every letter, held each one briefly and tried to accept that the puzzle of my mother’s death would never quite be solved.

The song ended and I carried the hatbox over and pulled all the 45s off the spindle and placed them in the bottom of the hatbox with everything else—now all my mother’s secrets, even the pink lipstick envelope, were in one place, ready to burn.

But as I covered it all with the crumpled newspaper page and prepared to set the hat on top, I saw something I’d missed before—a small hole cut into the paper. I unfolded the page and smoothed it out some, and there in the lower portion of page seven of the July 18, 1969 Lupoyoma Call & Record, was a rectangular hole, one column wide by maybe four inches deep, scissored out rather carefully judging by the fairly straight edges.

The hole was in the corner of an ad for Main Street Furniture, and I really didn’t think my mother had been shopping for a new couch. I turned it over to page eight, the back page of the A section, an assortment of local club announcements and social news, a few small ads. She had snipped something out of this particular page—maybe a friend’s engagement notice, or instructions for entering her cookies in the county fair, or even something she’d written herself.

It struck me as odd, even hard to believe, that whatever she’d clipped out had never turned up after she died. And the mystery of it broke the spell, pierced my sense of finality, my sense of defeat. It was yet another puzzle piece, but it might connect to other pieces, which might connect to the big picture I was trying to put together. I returned the paper to the hatbox and the hatbox to its place in the back of the closet. There’d be no fire today. You can’t burn away a question that’s stuck in your heart.

In the kitchen I opened the harvest gold fridge and found one can of cream soda behind a Tupperware bowl of leftover spaghetti. On the wall next to the fridge I noticed the calendar Darlene had brought home from the Bank of Lupoyoma. She’d tried so hard to fill it with exciting events which she marked with red scribbles and stars. It was Sunday, May 10, and in the appropriate calendar square, Darlene’s twice-underlined handwriting said “Santa Rosa!”

And the tiny capital letters printed in the corner said: “MOTHER’S DAY.” All day long, no one had mentioned it.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved