The Blues & Billie Armstrong 32

CURRENT EVENTS

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

Not a friendly peck on the cheek, but not a sloppy backseat makeout kiss either. Rather, a sudden, impulsive, sensuous kiss that looked like a question and an invitation. Billie didn’t look that surprised. Or interested. She just lightly pushed him away and laughed if off.

Predictably, it took an extra week or so for the national unrest to surface at Lupoyoma Middle School, but surface it did on Wednesday, May 13.

Unpredictably, Robyn the horse artist—straight-A student, student body President, yearbook editor—organized a small contingent of seventh and eighth graders to stage a walkout and declare a student strike in opposition to the war and the draft and the Kent State shootings.

Robyn stepped right up to Miss Lancaster during first recess and announced the plan, then more than a dozen kids marched across the playground chanting Strike! Strike! Strike! with ole Mancaster lumbering after them, threatening suspension and shouting that their parents would be notified immediately.

Craiger Robinson walked off the court in the middle of a dodgeball game and joined the protest, tugging his little brother Eugene along by the arm. Joey even took a few steps in that direction, but Timmy hurled the ball and nailed him in the back. “Where you going, asshat?”

I stood still, transfixed by this little breakdown of society, this intrusion of political reality on the sacred ground of junior high self absorption.

Joey walked over and stopped next to me. “You know, Robyn’s brother is over in Vietnam dodging bullets right now. And Craiger’s dad came home in a body bag last summer.”

No, I didn’t know.

We watched our classmates cross the outer boundary of the school and march into the neighborhood. Timmy spat on the blacktop.

Lead pressman Vic Pendergrass hit the startup button, the buzzer sounded, and the press lurched into action.

He ran to the folder and picked up the first waste copies of the weekend edition, ran around the press tweaking knobs, hurried back to the folder, checking image alignment and ink coverage. I stood at the end of the conveyor ramp and threw the waste into a wheeled cart.

The sound of the buzzer drew my father and Leslie McGoogan from their front offices for the official press check. They came through the swinging doors side-by-side. McGoogan said, “Big plans for you and the Mrs this weekend, Mike?”

And my father said, “I swear, she’s running me ragged, Les. Movies tonight. Dinner and dancing tomorrow. No rest for the weary.”

“Or the wicked, according to rumor.”

The press began building up speed like a locomotive, and my father and McGoogan stood on opposite sides of the conveyor, pulling copies off and quickly scanning for any stop-the-press errors in the editorial content or the all-important ads. Once they each signed off with a nod or a hand signal, their workday was done. Vic cranked up the press to full speed, and the jackhammering sound of it created that familiar cocoon of noise that shut out the rest of the world.

Vic was a short and stocky Black man who’d been a sergeant in the Navy and learned the printing trade on the G.I. Bill. He was living proof of that old saying about swearing and sailors. I’d never heard anyone curse like Vic Pendergrass. At times he made it sound like poetry.

While the press was running, my job was to gather the good copies in my arms and stack them in nearby bins, hurrying back and forth so papers wouldn’t back up on the conveyor. But carefully, because if you dropped an armload it could quickly turn into Lucy-in-the-candy-factory. And if you caused a slowdown or the press had to be stopped, or worse yet, if the press broke down, oh my. You’d hear, “Fuck shit piss god-dammity-damn!” And a wrench might take wing and fly across the room.

That particular Friday all went well, and following the A-section run, the press crew took a break. Stan and the new guy Don went outside to check out the chrome rims on Don’s 57 Rambler. “Revlon on a pig,” Vic said.

I stayed at my workstation and began slamming B-sections into A-sections. Vic turned on the shop radio and sat in the Linotype operator’s chair and lit a cigarette. He smoked non-filtered Lucky Strikes that smelled like manure on fire.

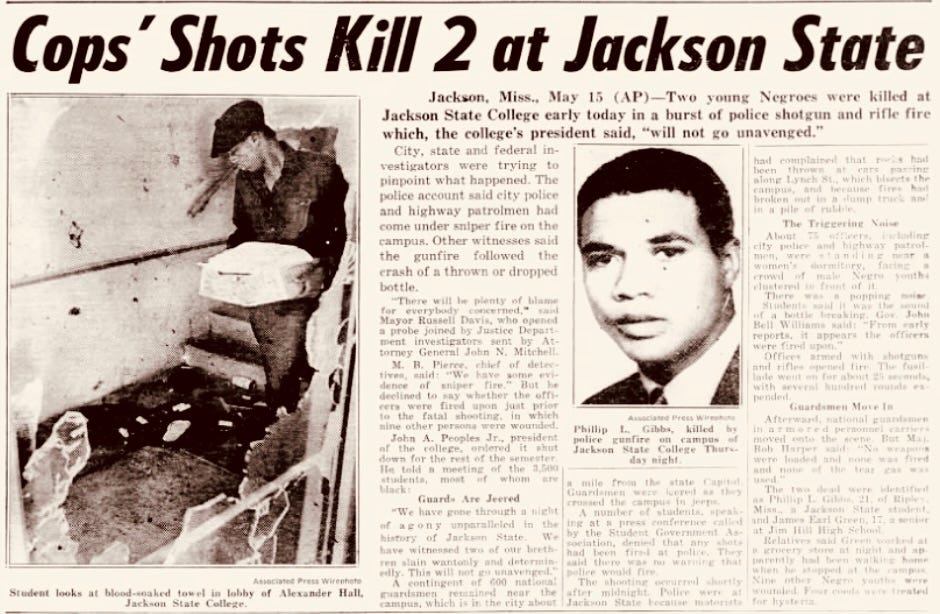

On the radio a newsman said two more students had been shot early that morning during an anti-war demonstration at Jackson State University in Mississippi. At first he said “two Negro men were killed,” and did not give their names. Later in the broadcast he identified them as twenty-one-year-old law student Phillip Gibbs and seventeen-year-old high school student James Green. “Men, my black hairy ass!” said Vic. “Jesus-goddamn-Christ! Couple schoolboys is more like it.”

The radio said the police claimed a sniper had fired two shots at them. Therefore they unleashed hundreds of shotgun blasts that happened to kill Gibbs and Green and wound twelve other people. But no snipers were reported shot, or arrested, or chased, or identified by the police or any other witnesses. Vic threw down his cigarette and stamped it out with his work boot. “What in the holy blue fuck is happening to this country!”

By the time I headed down Fourth Street, I could see the porch light was on although the sky wasn’t dark yet, a clear sign the parents had gone out and the house was empty.

On the kitchen table, Darlene had left a needlessly detailed note that they were off to see Paint Your Wagon, and she’d written step-by-step instructions on how to take a TV dinner out of the freezer, preheat the oven to the desired temperature and pull back the foil on the fried chicken at the proper time, plus a reminder to turn the oven off when the cooking was done and leave the porch light on when I went to bed. The note was signed with a big buxom capital D.

I didn’t have the patience to preheat the oven. I did pull back the foil on the chicken, then dialed up 450 and threw in the dinner, went to the living room, set up a TV tray and flipped on the television.

Nothing but the six o’clock news on all three channels. Just the major networks, that’s all we had in 1970 Lupoyoma. Three channels of fiery columns of black smoke and roaring napalm jets and dirty grim-faced soldiers that used to be kids. Caskets and body bags issuing onto the tarmac from the bellies of planes. Screaming demonstrations, walkouts and strikes, marches and riots. Soldiers with rifles and bayonets ready, crawling across campus lawns. Police with tear gas and billy clubs and shotguns and shields. Students with signs and slogans and bottles and bricks. Working class joes with baseball bats and uppercuts. Fat greasy politicians grandstanding, namecalling and fearmongering.

Everybody angry. Everybody lying. Nobody listening.

“This motherfucking war,” I said to Cronkite.

And I turned off the television and finished my unevenly cooked Swanson’s Fried Chicken Dinner in the darkening silence.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved