The Blues & Billie Armstrong 5

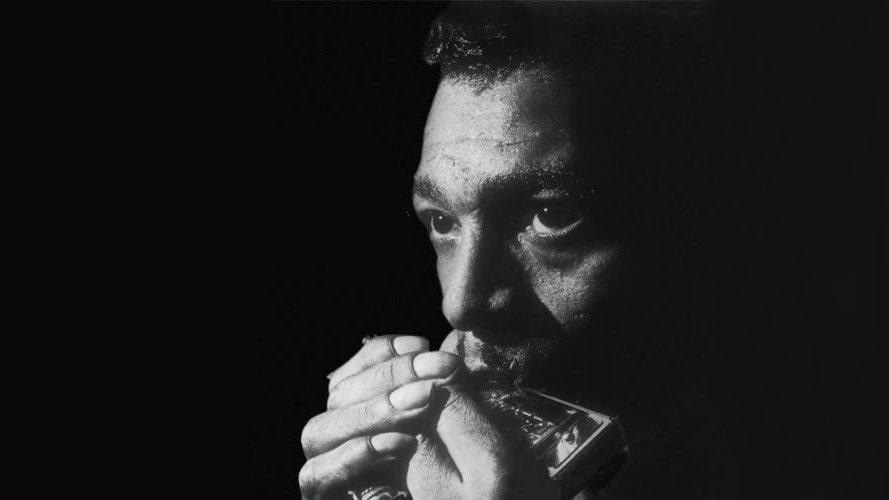

LITTLE WALTER JACOBS

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

I made a right turn down Third Street, deciding I would slip through our back fence again and hide out at home. But down the sidewalk I saw the sandwich board advertising the local music store, The Music Box. I stopped, bent over at the waist, hands on knees, caught my breath.

Nate Henderson was a nineteen year old kid whose parents owned The Music Box.

He’d been considered a bit of a geek in high school, even though he played in a local rock band—the kind of guy who couldn’t look cool even with a guitar in his hands. After Lupoyoma High, he’d gone to Santa Rosa Junior College to study business (and evade the draft), but he still helped out at the store whenever he was in town. I’d never actually met him before, but back then Lupoyoma was a snowglobe of a town, where everything seemed to be within five blocks of everything else and everyone knew the TV Guide version of your life story even if you’d never spoken directly to one another.

I walked in the store, approached the counter and asked Nate if he’d ever heard of a song called Sad Hours. Nate was a tall, skinny guy, with brown wavy hair almost to his shoulders and parted sharply on the side so it cut diagonally across his face and sometimes obscured one eye. He asked who the recording artist was, and I had to say I didn’t know—looking at the record on the turntable I hadn’t focused in on anything but the title. Nate plopped a big thick catalog on the glass countertop and thumbed through its pages, stopped and shot me a look of mild surprise.

“So, how’d you hear of this song anyway?”

“I found it on my mother’s record player.”

He brushed his hair aside. “No way. Trini Lopez, Sinatra or Streisand for your dad’s birthday, but she never bought anything like this that I know of.”

“So, what is it?”

It turned out the horn I’d heard was actually a blues harmonica player known as Little Walter Jacobs. Nate showed me a picture beside the listing in the catalog. Little Walter Jacobs was a black man with a hardscrabble face and big haunted eyes. I’d associated the harmonica with campfire songs and Bob Dylan. I had no idea it could be made to moan and shout and protest all the disappointment of the world.

Until that moment I didn’t even know enough to label what I’d heard in the dayroom as “blues.” Even with my mother’s Mexican blood, I was basically a green white kid from the hills of Northern California. I was so white I didn’t know the blues was black. I only knew it stabbed me in the heart in some way no other music ever had and it mystified and worried me that it was apparently so meaningful to my mother.

Nate said Sad Hours was originally released in the early fifties and was already something of a rarity. He said that kind of blues was way out of style these days. Little Walter had died a year or so before and all his singles were out of print. There was just one album listed in the catalog, which Nate could order, but I didn’t have the four bucks for that, not to mention I didn’t even have a record player of my own.

I thought of my mother singing Lemon Tree along with her Trini Lopez album while ironing my father’s shirts, and I couldn’t help but wonder how she would come into possession—or even awareness—of such an oddity as Sad Hours, which seemed so out of place in her world and in our home, a musical interloper. And could Little Walter’s harmonica be related to the pink lipstick on the back of that envelope?

I thanked Nate for the info. He said “By the way, sorry about your mom, kid.” And I left the store and headed down Third Street toward the lake. I took the shortcut across the Yacht Club parking lot and back through our fence with the odd feeling that I was sneaking into my own house.

I had the idea to get back into the dayroom—now, while the adults were gone. The past few days had felt like our home was quarantined with disease. I was ordered not to leave the property and not to have friends over. No one outside the family came to visit. Grandma Junia manned the kitchen sink, dusted the living room furniture, created small corners of routine and conducted muffled conversations on the yellow phone.

My father left early for work, came home late and sat in the nervous television light with the sound down low. He rarely spoke and was rarely spoken to. He drank and watched TV with a stare like he was looking right through the picture. Molly dutifully appeared at the front door one evening to deliver a glass casserole dish of Pop’s famous enchiladas while Pop waited in the Chevy pickup parked at the curb, with the motor running and Hank Williams honky-tonkin on the radio. At other times, Aunt Laurette had flitted in and out of the house on missions for Grandma Junia—to the market with a list, to the dry cleaners with funeral clothes.

And, all along, the door to the dayroom stayed closed in a forbidding way, with the adults guarding it peripherally as they went about their quiet preparations. There seemed to be an unspoken understanding that the room should remain undisturbed.

But now I stood at the closed door of the dayroom, doorknob in hand, my heart running wild and snapshots of memory flashing behind my eyes like tiny fireworks. I couldn’t seem to turn the knob. In the center of my skull I heard the staticky scratch-scratch as if the needle was still stuck at the end of that record and my mother still lay on the bed. I could not will my wrist to perform the motion to turn the knob and open the door. My body simply wasn’t ready to be alone in that space again, to re-live those first minutes of knowing—and the swarm of questions, the not knowing, that followed.

I had figured someone would come looking for me after I ran out of the funeral, and I knew sooner or later they’d look for me at home. I thought Grandma Junia would probably delegate the errand to Laurette as she had before. But I heard the low grind of Pop downshifting the old Chevy truck and the squeal of the brakes as he brought it to a halt at the curb outside. The motor grumbled to a stop and the truck door closed with a thunk.

I only had a few moments before he would make it up the walkway and through the front door.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved

This has to be the best way to publish a novel ... Nothing new about the graphics, but sound, too? What a production! What a presentation!