The Blues & Billie Armstrong 57

THE EDITOR'S LAST CORRECTION

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

“I’m not sure I see the point in showing up for one last argument with him.” I said. “Hey, no judgement,” Sonny said. “Point is, I know she would like to see you.” I let that suggestion fall and kept walking up Main Street.

The Giants were in the National League Championship Series against the Philadelphia Phillies, and I had missed the first couple games sweating out that two-day hangover in a San Francisco jail.

By the time Sonny and I made it to the Weeping Willow parking lot, game three was about to start, and I was going to watch every pitch, hell or high water, as Pop would say. And damn the rest of the world.

I sat at the bar, sipped my way through a couple beers and a couple bourbons, watching on one of the big screen TVs. My old “friend” Craiger Robinson, now Sonny’s right-hand man, was tending bar. We clinked bottles and swapped Little League war stories and what-you-been-up-to-since-way-back-when stories.

I knew there was a small, albeit unconnected, cadre of people who were at that very moment in a butt-clenching hurry to see me, question me, order me, threaten me, but I’d left my dead phone in the Cadillac, and no one in the bar except Sonny and Craiger knew who I was. I was drinking incognito, and that was good, because I needed time not to think.

The series was tied one-one after the first two games in Philly. A win in their first home game could be crucial for the Giants. And they delivered. Starter Matt Cain threw seven strong innings, and Javiér Lopez and closer Brian Wilson slammed the door on a three-nothing victory. The Giants were up two-one in the NLCS! I wondered if my father was watching.

I had the bothersome idea that I should probably get back in touch with the rest of the world.

I sat in the parked Cadillac and started the engine to charge up my phone.

The great Howlin’ Wolf, came blasting out of the stereo singing, Moanin’ at Midnight—that pained and gutwrenched roar of his, like a man pouring whiskey on his own stab wound. Somebody’s knocking on his door, and he does not want to answer.

When enough juice reached my phone to bring it back to life, the thing went off like a clock store at the top of the hour. Repeating triplets of chime-ding-bloop, chime-ding-bloop. I let it all tally up like a slot machine jackpot: seventeen text messages, nine voice mails, twelve emails and six Facebook messages. Then I yanked out the charging cable and threw the phone over my shoulder. It bounced off the back seat and thumped on the floor. Meanwhile, Howlin’ Wolf’s phone is ringing off the hook.

I should’ve known what was coming.

After all, I knew I’d missed the deadline for the Billie Armstrong story. By now her arrest and mugshot were already hitting front pages and cable news everywhere. There would be a series of questions from Tom Monihan, turning into demands, leading to outright begging and finally a profane tirade. There might be an email or two from Daniel Lockhart himself, containing some threatening legalistic googlymoogly about contractual obligations and the company’s recourse for breach.

And I knew Billie had been transported to a federal facility in San Francisco and was being held without bail. The pair of FBI agents who questioned me in jail that morning had filled me in on that while making it clear that, although I was being released, I remained a “person of interest” for possibly aiding and abetting a fugitive, and I could easily be in the same situation as Billie if at any time I chose not to cooperate to their satisfaction.

Lastly, I knew of course that Valentine Jones would be expecting to hear from me. I knew she would want me to sign an affidavit and agree to testify in court if necessary, plus she would probably want to talk to death the secrets that had poured out in the bar.

Not now, I thought. Not right now.

I put the car in reverse and backed out, turned the stereo up and drove under the old arch of oak branches and out of the Weeping Willow. Howlin’ Wolf came in for the big finish—don’t worry, he said, “Daddy’s gone to bed.”

I’d always thought that was such a bizarre non sequitur—but now it struck me as accidentally prescient. I’m a rational man. As I’ve said before, I am not a believer. I have no faith in faith. And I won’t try to be on both of sides of that fence by claiming to be “spiritual but not religious.” I’ve been in barfights over such things. And yet I can be as superstitious as an old third base coach. I pay attention to certain signs—musical omens and portents—that others would call coincidence. The right words in the right song, blasting out of the right stereo speakers at the right time, can briefly take control of my state of mind, my car, and thus my life.

The yard at the old house on Fourth Street was a sad mess.

The lawn overrun and the walkway threatened by a gang of dandelions and their weedy associates, the rosebushes in front of the porch all thick and tangled and thorny Medusas. Aunt Laurette sat in the old wicker chair on the porch puffing on a cigarette.

She saw it was me climbing out of the Cadillac, and she screamed and waved and threw down her lit smoke and hurried down the steps. “Archer King, I swear, your ears must be on fire! I was just talking about you.” The years had stripped away her figure and she was now a small thin woman with a big hairdo that was not naturally black. She wore a tight leopard print blouse with white skinny jeans that emphasized the sticks she had for legs. Still sporting her trademark blue flame eyeshadow.

She met me on the sidewalk and gave me a long-lost kind of a hug, stepped back and looked me up and down. “Boy, you look like hell,” she said. She gave me a wink like the kind she could always embarrass me with in younger days.

“I was in town…” I said, and I looked down and toed at a dandelion in the seam of the sidewalk. “and I thought maybe I should see him.”

“Well, I think you should,” she said and patted me on the arm. “But I’m not sure he’ll agree.”

“What do you mean?”

Laurette winced like she wanted the words back. “I mean he might not know who you are. The hospice nurse is with him now, he’s unconscious a lot, and even when he’s awake he’s confused… and he can be a cranky pain in the ass.”

I didn’t respond, unsure if I was disappointed or relieved.

“We’re talking days, maybe hours now,” she said.

“Got anything to drink?”

She shook her head at my obvious dissipation and waved for me to follow her up the stairs and into the house, through the old wooden screen door with the screen peeled back from the frame in one corner. She held a finger to her lips and whispered, “Wait here.”

The curtains were closed and the stale dim smelled like cigarette smoke and mildew and piss. I heard muffled voices drifting up from the back of the house and then my father hollering in a voice almost unrecognizable. “I said no visitors! Make them go away, goddammit! Fucking ghosts. Don’t let them in my house.” Words spat out in gasps between hacking gurgling coughs, words like ground up rocks shot out of a cement mixer.

Then the nursing and shushing voices of the two women. A duet of calming reassurance.

Laurette came back, shrugged an apology and waved me into the kitchen, signaling me again to keep quiet. She wiped the dust out of two glasses with a dish towel and poured in some Seagram’s 7. “He says a lot of weird shit these days,” she said.

We sat and sipped whiskey and spoke in hushed tones among the litter of pill bottles and paperwork piled up on the table. When the coughing quieted down, Carla the hospice nurse came out and stood by the front door with a pack of cigarettes and a lighter. She was a plump Mexican woman with wavy hair and beautiful eyes dark as a tall glass of Guinness. “I gave him another shot, he will sleep now,” she said with a sad careful smile, and she stepped out to the porch.

Laurette stubbed a cigarette out in the overpopulated ashtray. There was a cardboard file holder, the kind with accordion folds, propped up on one of the empty chairs, and she lifted it to the table and flipped open the cardboard lid. She pulled out a small manilla envelope, maybe six by nine inches, and set it down in front of me. It had my name written on it. Just my first name, in black felt pen, in a spindly shaky hand.

“My inheritance?”

She didn’t laugh. She lit a new cigarette, aimed a stream of smoke at my face. “One day I heard a crash,” she said. “And I ran in there and found him on the floor over by the file cabinet. He was holding that envelope, and he told me to be sure you got it after he’s gone. But who the hell knows when I’ll see you again, so…” She left me at the table and took her drink and cigarettes out to join Carla on the porch.

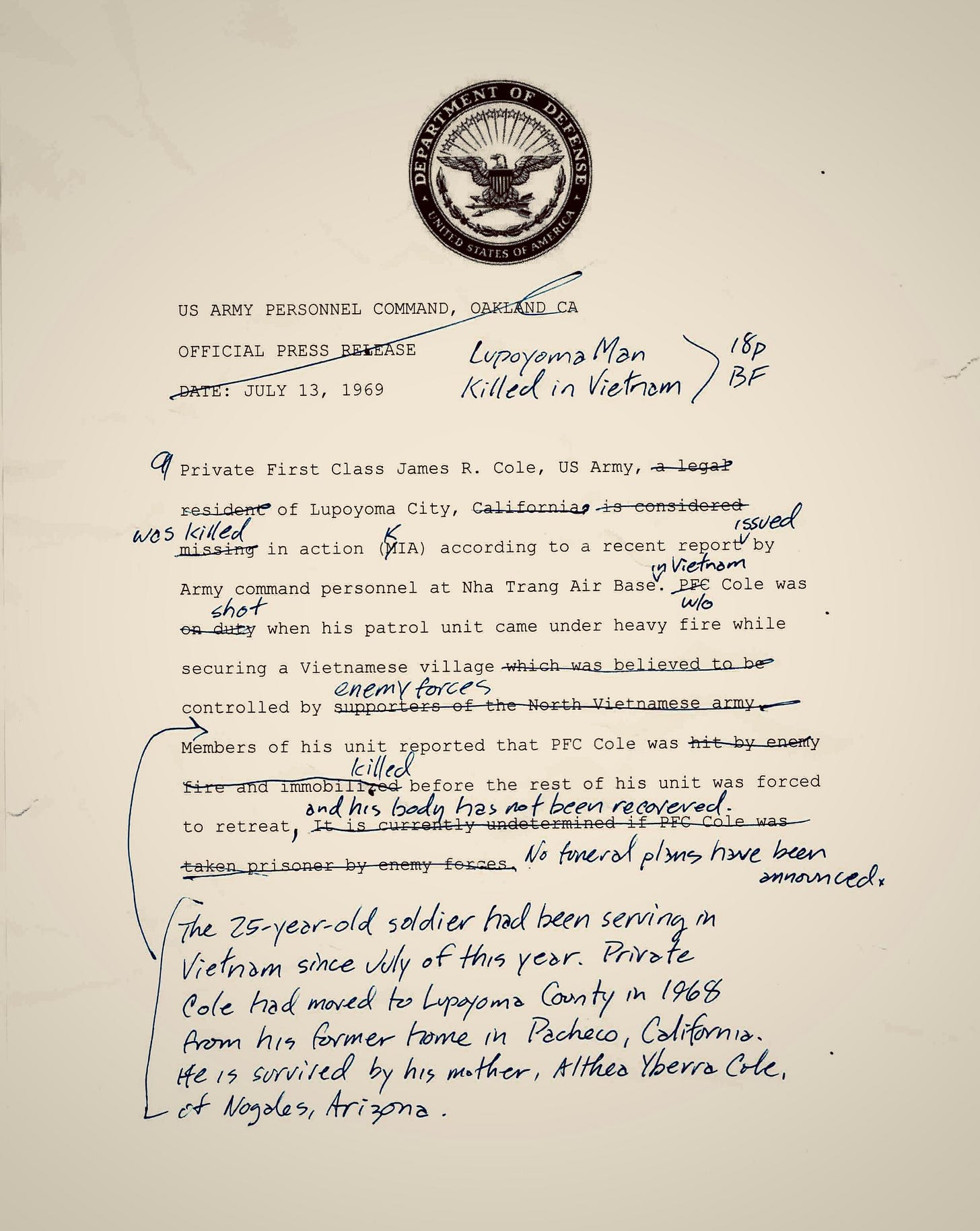

I poured another inch of whiskey and opened the envelope. I was expecting some sort of legal document, but inside was a single folded piece of cheap typewriter paper like I remembered from my early days in the offices of the Call & Record. I unfolded it and saw a U.S. Department of Defense logo and a block of type in fading black ink.

In effect, these were my father’s final words to his son.

US ARMY PERSONNEL COMMAND, OAKLAND CA

OFFICIAL PRESS RELEASE

DATE: JULY 13, 1969

Private First Class James R. Cole, US Army, a legal resident of Lupoyoma City, California, is considered missing in action (MIA) according to a recent report by Army command personnel at Nha Trang Air Base. PFC Cole was on duty when his patrol unit came under heavy fire while securing a Vietnamese village which was believed to be controlled by supporters of the North Vietnamese army. Members of his unit reported that PFC Cole was hit by enemy fire and immobilized before the rest of his unit was forced to retreat. It is currently undetermined if PFC Cole was taken prisoner by enemy forces.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved