The Blues & Billie Armstrong 7

WHAT ABOUT THE BOY?

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

Doc Meaney would have to be called in to treat my overwhelming growing pains, and I would be told there was no cure, that I would for all intents and purposes be a grown man in a matter of months. And then I would begin to see through new eyes all the things I’d been told for so long I was too young to understand.

It was running out of my mother’s funeral that led to my first job in the newspaper business.

Well, that and the fact that Hank Timmons had recently received his draft notice.

In 1969 Lupoyoma it was thought obvious that an adolescent boy could not be properly looked after by a single, professional man with a responsible position in the community. According to Grandma Junia, I would soon be running wild in the streets, a hoodlum with a switchblade in my back pocket and a delinquent girlfriend on the reservation south of town. I had already given weight to this theory with my “disappearing act” at the funeral.

At first, Grandma Junia answered the call to duty like a reluctant general hastened out of retirement. On school days she left work early and arrived at our house before I came home. The big Buick would be parked in the driveway. She would mutter in the kitchen, rummage the shelves and rustle and clang about while I sat on the living room sofa watching afternoon cartoons: Rocky and Bullwinkle, The Jetsons, Underdog. I was seeking refuge in familiar comforts of childhood, and Grandma Junia briefly—and surprisingly—indulged me.

She would call me to the table around five o’clock, and my plate would already be in place, the Giants logo glass on my right, filled with cold milk. She cooked sturdy midwestern dinners that always included meat, potatoes and corn. Having lived through the Great Depression, this was her idea of bounty—and as close as she came to nurturing.

She had the knack of making love seem like a favor. She was visibly inconvenienced by the demands of family and sometimes held audible debates with herself over the things she was willing or not willing to do for others. Still, she loved me in her own tight-lipped fashion, and I believed she was trying her best to soften the blow, trying to ease my transition into life as a motherless boy. But this grim simulation seemed an uncomfortable stretch for her, and before long she made it clear it was time to re-involve myself with the so-called real world.

One evening in late October, several weeks after the funeral, my father and Grandma Junia were sitting at the oak table in the yellow kitchen enjoying after-dinner highballs and cigarettes. When I entered the room, she leaned sideways to talk to my father but kept her eyes squarely on me. “So, Michael, what about the boy?” she said.

My father took his glasses off—thick black frames with bifocal lenses—and stared down at the garish vinyl flooring and rubbed the bridge of his nose between his thumb and two fingers. He was the kind of man who was pained by not having a ready answer. Yet there seemed to be none; my mother was dead and my father was a newspaperman, both afflictions apparently permanent.

Hank Timmons was eighteen, practically a kid like me.

I’d met him at the funeral. He was one of several staffers from the Call & Record who stood in line on the porch to shake hands with my father.

“Sorry for your loss, Mr. King,” Hank had said, as if he’d just learned the phrase. Eyes down, feet shuffling like he couldn’t bear to stand still.

My father said, with a hint of fanfare, “Son, this is Hank Timmons. He works at the paper in the back shop.” Of course, I already knew who he was, and my father was well aware that I knew who he was. He was a local legend—probably the greatest athlete Lupoyoma High ever produced, certainly the greatest baseball player.

I’d watched him play since he was the star of the Call & Record’s Little League team. Back then my mother volunteered as the team’s scorekeeper, and when I was six or seven years old that was my introduction to the game. I tagged along and sat beside her in the small stand of wooden bleachers. I ate boiled hot dogs and grape snowcones and chased foul balls that went into the creek. And my mother allowed me to look over her shoulder and ask long strings of annoying questions.

In that way I began to learn the intricacies of the game and how to record them on a scoresheet. During those years, Hank Timmons was an absolute phenom, the personification of the old cliché, “a man among boys.” He once blasted fourteen home runs in a twelve-game season, to this day the Lupoyoma Little League record.

Hank shook my hand and said, “Well, uh… sorry for your loss, bud,” apparently surprised to be cued for a second performance. His wheat-blonde hair was short and uncombed. He wasn’t wearing a suit like the full-grown men, just gray slacks, a white dress shirt with a tie, and his Block L varsity jacket. He looked me over. “Nice suit,” he said, with a sarcastic but sympathetic nod.

“Thanks,” I acknowledged, with a grateful eye roll. I had the feeling I’d just met an old friend, and I had a lot of questions I wanted to ask, like how to throw a curveball and what about those fourteen homers, but I didn’t want a lecture from Grandma Junia about this not being the proper time or place.

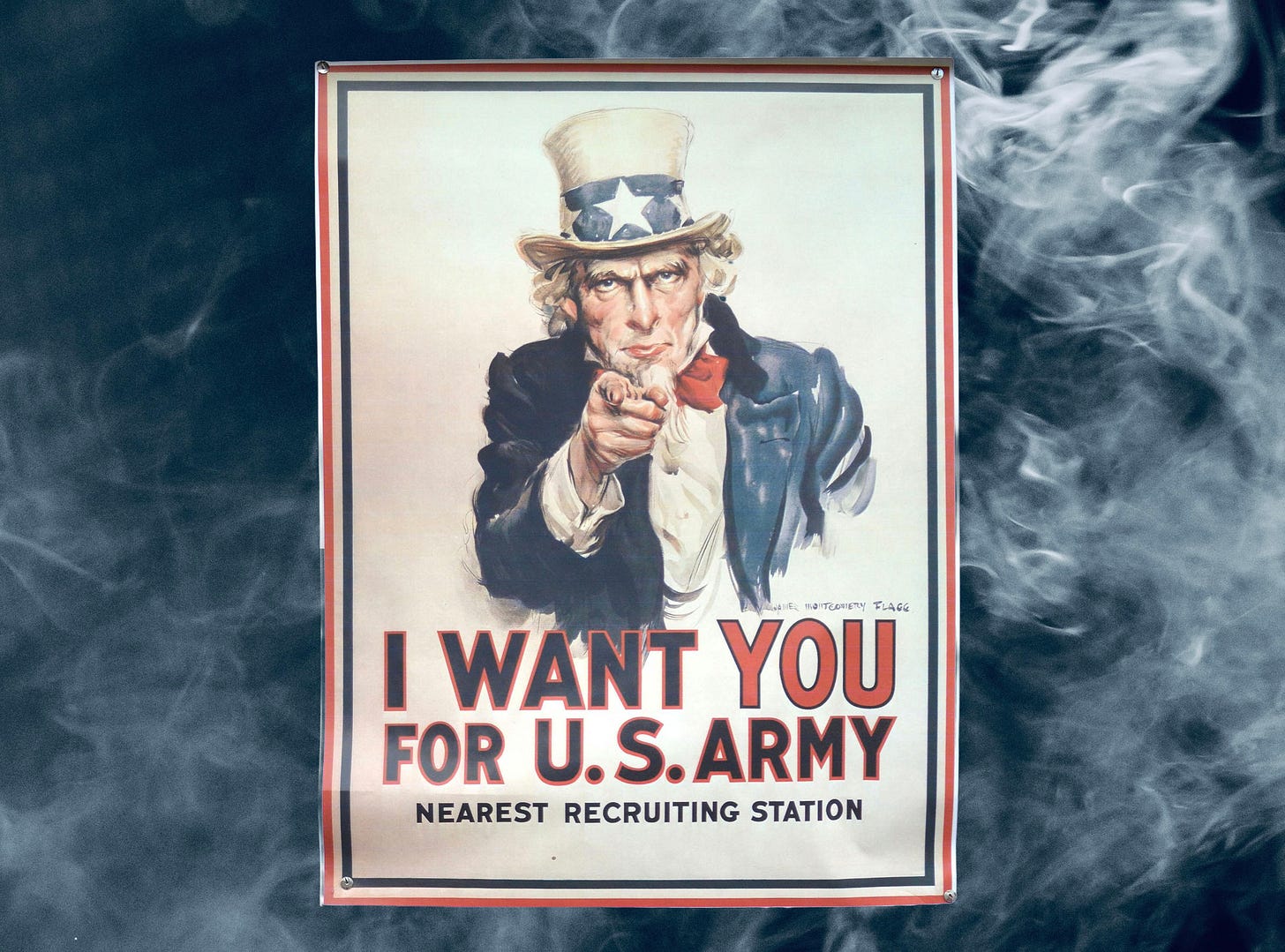

“I understand Hank Timmons is due to report to the Army soon,” Grandma Junia said, still looking across the kitchen at me in her calculating way.

“It’s no surprise,” she went on. “He should have taken his studies more seriously. It was only a matter of time before Uncle Sam came calling.”

“At least he’s not one of these goddamn draft dodgers,” my father said. “Not a bad worker, either. He’ll be missed.”

Grandma Junia had a way of tilting her head down as if the movement started in her chin, and at the same time raising the Buick eyebrows slightly as she pursed her lipsticked mouth. This practiced expression was Junia King’s version of a kick in the shin under the table. And in that way, with her eyes moving back and forth from my father to me, it was “suggested” that I be considered as Hank’s replacement at the newspaper ahead of his leaving for basic training.

My father put his glasses back on and looked my way. “The boy’s just turned thirteen,” he said. “He can’t even get a work permit until next year.”

“Nonsense. Weren’t you the same age when you started in the business?”

“That was a different time. There are laws now, and our boss won’t—”

“You leave the boss to me.”

My father nodded slowly, indicating reflection. “I suppose a little hard work would do him good, maybe take his mind off things.”

It was no surprise that my father thought of work as the best available grief therapy for his son—hard work will do you good was essentially the cornerstone of his philosophy of life.

Grandma Junia brushed her hands, “Well then… that’s that.”

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved

Chuckle, LOL ... I recognize these people ... the names have been changed ...