The Blues & Billie Armstrong 9

A FRATERNITY OF DEVILS

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

Hank lifted a grungy, soiled apron off a hook on the wall and held it out to me. The thing had once been white, but now was yellowed and slick with sweat and ancient ink stains. “Here,” he said, “you’re gonna need this.”

He handed me a whiskbroom and dustpan and led me to another part of the shop.

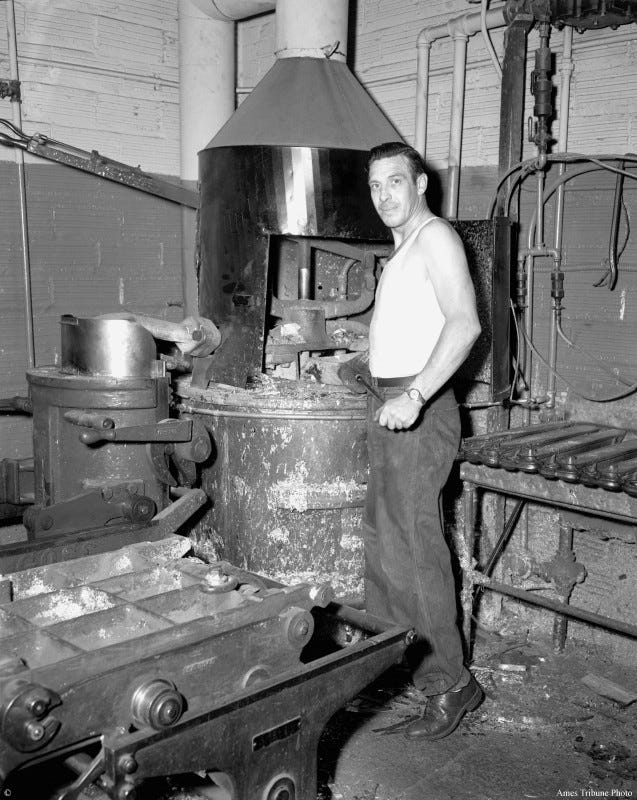

We stopped in front of a huge mass of machinery with more parts than an illustration of human anatomy. It was five feet across and eight feet high, a tangled wall of belts and levers and switches, and wheels and gears and gauges, and handles and buttons and knobs. At the center of it all a gooseneck lamp grew straight out and hung over a big keyboard that looked like a typewriter with a thyroid condition. An empty office chair was rolled up next to the keyboard, dwarfed by the behemoth it was in position to control.

According to the raised letters on the machine’s nameplate, this wondrous monstrosity was called a Linotype. I assure you, if any real machine in all the world was the inspiration for Rube Goldberg’s beloved cartoons, it must have been a Linotype machine.

I said, “Jesus Christ, what does it do?”

Hank pointed to a stack of five or six metal bars on the floor next to the machine. They were silverish looking ingots, about two feet long and thick as my forearm. Each one had an open loop at one end.

He said, “These are called pigs—don’t ask me why. They’re made of lead and they go on the hook at the end of that chain there, and that chain lowers them down into a little melting pot inside the machine. The melting pot melts the lead and the machine turns the melted lead into lines of type. And don’t ask me how. Nobody in the whole shop really knows—except Terwilliger, your dad, and Vic.”

“My dad runs that thing?”

“Yeah, when Vic is out or busy with something else. But the important thing for you is the pigs.”

“Got it,” I said. “I’m in charge of the pigs… but why am I called a printer’s devil?”

Hank looked at me like I was from Mars for even asking. “Hell if I know!” he said.

He had me sweep up the metal shavings that carpeted the floor around the Linotype and dump them into something he called the hellbox, sort of a wastebasket where used and rejected type was collected to be melted down. It was made of scarred and darkled old wood, its four sides held together by aging metal el-brackets. Time had pried open narrow gaps at the seams, and when Hank had me carry it to the compositor’s table, powdered metal spilled out like silverdust.

He taught me how to break down yesterday’s pages and add the used type to the rickety hellbox. Then he led me into the room known as the forge room, or simply, the pig room. It was a dimly lit space maybe ten feet square, with a low plaster ceiling.

Metal pipes ran up and down and across the walls. A gray iron cauldron squatted in one corner like a witch’s brewpot. Drips and splashes of metal had cooled and hardened on the outside and clung to its belly like quicksilver in freeze-frame. The floor was littered with misshapen puddles of hardened metal, stray chunks of type, and shining splinters and powder. Inside the ducting above the melting pot, a wobbly fan went whup-whup-whup like a helicopter in the distance.

Hank raised his voice, “Never-ever forget to turn the fan on when the forge is lit. These fumes will knock you out like Joe Frazier, understand?”

I understood. Even with the fan going, every breath was bitter with the stench of boiling chemicals that tightened your throat like asthma. And the heat! My own theory about the term, “printer’s devil,” is that it must have been the shocking heat of the pig room that brought hell and the devil to mind. I wiped my forehead with the back of my hand. “Jeez, how hot is it in here?”

Hank laughed. “It’s a hundred-and-fuck!”

He had lit the gas flame on the big melting pot and dumped in some type before I arrived. He threw in a hunk now and I watched it start to melt and disappear into the leaden sea like the Titanic. He shouted over the fan, “Type lead melts at 425 degrees. 425 degrees is seriously hot, bud. Serious as a heart attack, ya hear?”

He showed me the four iron pig molds on the floor and the big iron ladle hanging from a nail on the wall. He pushed me up to the edge of the pot and coached me to use the ladle to scoop the dross off the surface and fill the molds with the liquid metal. The dross was gray scum, wet and thick as November mud. It bubbled and popped and occasionally spit into the air. I was wearing gloves, but a drop spattered my forearm and I yelped and dropped the ladle to the floor.

Hank looked askance, and I showed him the new chuckhole in my arm, edged with multiple layers of cooked skin. He laughed like a goof and dismissed my wound with a wave. “Ya get used to it.”

I laughed with him, ignoring the sting. I wanted to be a working man like my father and live up to the ink that Mr. Terwilliger said was in my blood. And I wanted to impress Hank, to be one of the boys, one of the crew like Vic and Stan.

My father had taught me that work was character-building duty. Hank Timmons taught me that work could be play. He made sweeping, dust-mopping, vacuuming, and even pig-making look like athletic events. He could pick up a trash can on the run, carry it outside, empty it in the dumpster and run it back to its place in less than ten seconds. He had the grace of a fine shortstop and the brute strength of a linebacker. I would never meet another man so at home, so at one, with his own body, so naturally mindful of its possibilities. He was walking around inside the best machine in the world and he knew it, although at that time perhaps in a more innocent way.

I turned off the gas, and the flame sputtered out. Hank switched off the whup-whup fan, and we left the newborn pigs to cool and harden.

I felt different walking home that day. Bigger. I was dirty and tired, damp with worksweat, and unconcerned about seams in the sidewalk. A group of geese is a gaggle, a group of crows is a murder, a group of young pigs is called a drift. Perhaps a group of devils could be called a fraternity. I’d been schooled and hazed and rightfully initiated into that fraternity, alongside Jefferson, Franklin and Twain. And Hank and my father.

I felt I had crossed an important barrier and entered the proud society of working men, where I might become tough and resilient in the face of injury and self-possessed in the face of danger and stress… and loss.

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved

That's the best description of a Linotype I've ever heard.