The Blues & Billie Armstrong 20

QUICKSAND

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

I blurted out loud, “You know, when someone dies you can lose things you never even had.” I didn’t even open my eyes to check, but I knew Billie had heard me because she turned up the music until I felt the bass notes rise up from the floor and shiver in my chest.

We stayed in the room all day listening to the records again and again.

Big Mama, Little Walter, Memphis Minnie, Muddy Waters, T-Bone Walker, Howlin’ Wolf and more. We listened to them all, then flipped them over and listened to the B sides as well. We never got dressed, never turned on the TV, forgot to eat.

We smoked the longest cigarette butts we could salvage from ash trays around the house and when it got warm in the afternoon we went to the kitchen and made grape Kool-Aid, which Billie spiked with some of the gin that Grandma Junia kept in the cupboard. We brought it back to the room in tall yellow Tupperware glasses.

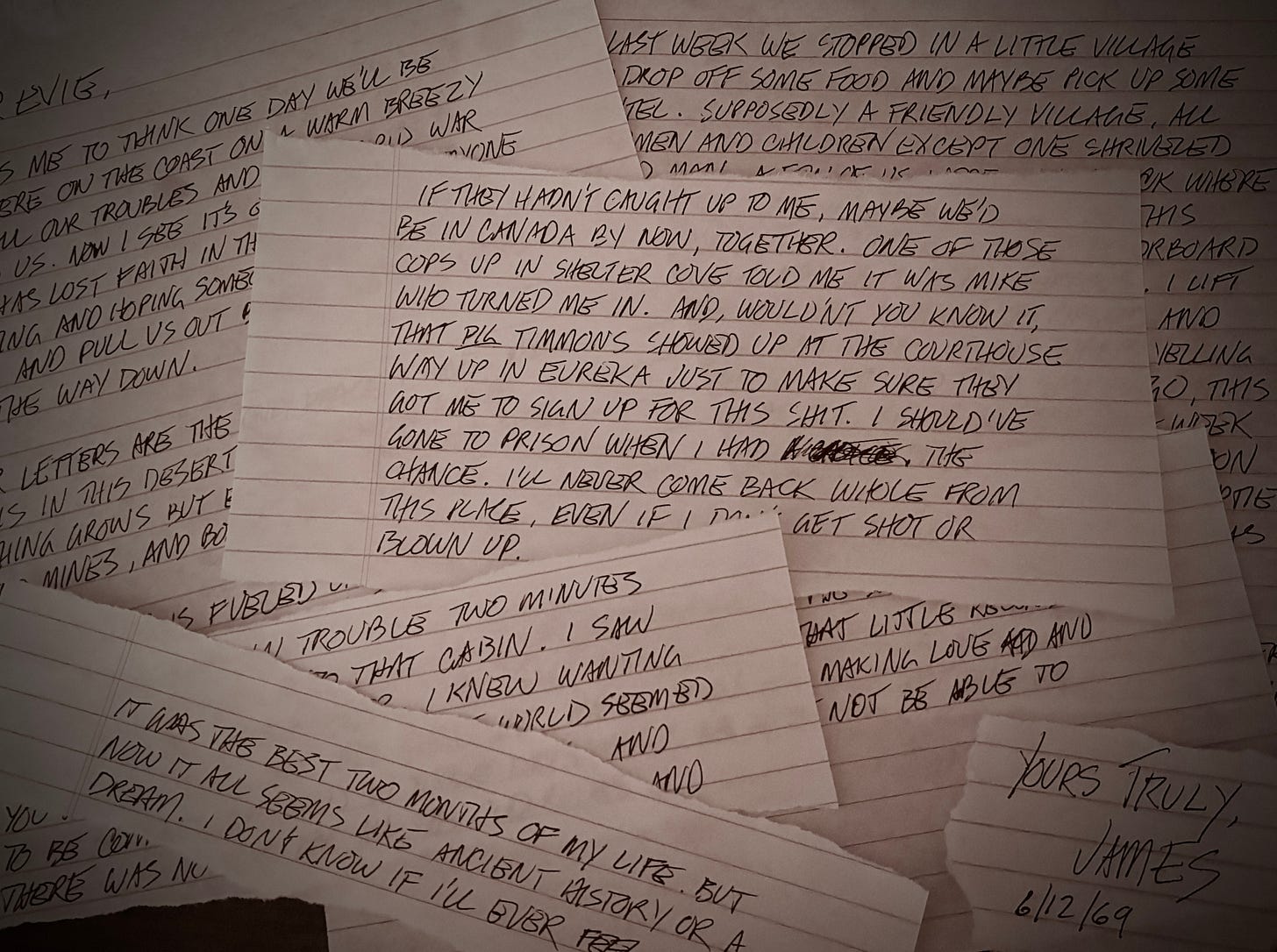

I sat at the vanity and refused to read the letters, but Billie chose bits to read aloud, and I was powerless to stop her. She turned the music down and walked the room, curating and commenting while the blues grooved underneath like a soundtrack, and after a while I stopped resisting and started listening to the story the letters told.

“Wow, your mom worked for Bobby Kennedy?” Billie didn’t wait for an answer, but I remembered my mother being excited to be the local chairperson of Kennedy’s campaign that spring, and how she’d set up an office in a cabin at the Weeping Willow Resort & Trailer Court.

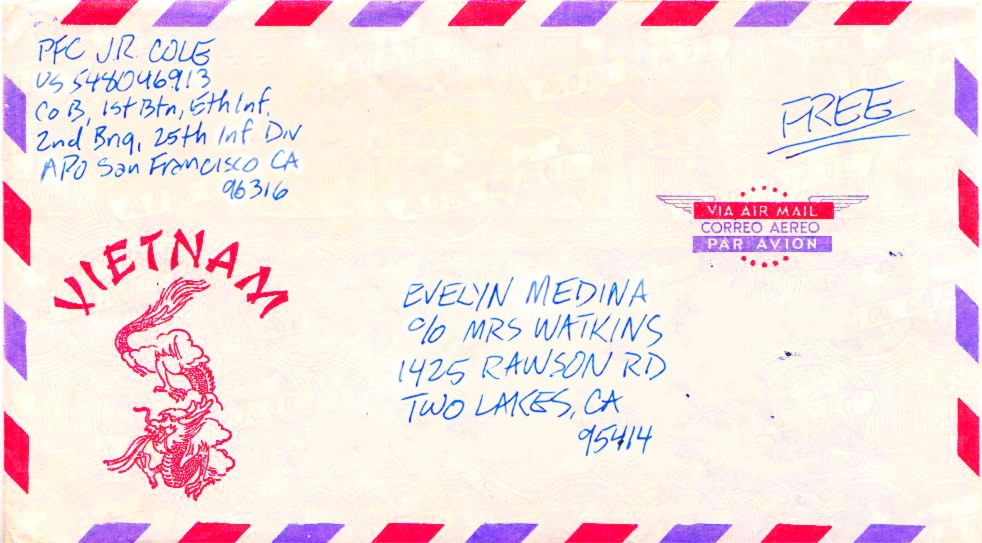

“That’s how they met,” Billie said. “J.R. came to her office the day after Martin Luther King was assassinated. He wanted to sign up and volunteer but listen to this—he says, I knew I was in trouble two minutes after I walked into that cabin. I saw the ring on your finger, I knew wanting you was wrong, but the whole world seemed to be coming unhinged in those days, and there was no time for all the old rules.” And Billie added, “Yeah man, no time for rules!”

“I’m not sure I want to hear this,” I said.

I resented the way Billie seemed to thrill at the unfolding story like an old romantic movie, and yet she managed to annoy and entertain me at the same time. At one point she parodied the voice of a melodramatic pitchman. “Presenting a heartrending story of star-crossed love in the midst of national turmoil, with Elizabeth Taylor as the lonely, passionate Evie King, and James Dean as the troubled soldier, J.R. Cole.”

It was some natural-born sleight of hand the way she mixed the uncomfortable details with comic relief so that I was distracted from the mob of emotions rioting in my head—over the letters, the records, the dayroom memories, and Billie herself.

“They fell in love working on the campaign,” she said. “He talks about walking all over town with her, putting up posters and signs, ringing doorbells stumping for Kennedy. And one time they drove down Main Street during the Memorial Day parade with a big Kennedy for President banner on the side. It’s like he’s reliving their time together. And he says, It was the best two months of my life. But now it all seems like ancient history or a dream.

“Oh and here’s some more about the records. I’ll never forget that night we stayed in watching the news with the sound off and the blues turned up on that little record player, making plans and making love and—”

“That’s enough,” I said.

Billie waved me off. “Stop judging her.”

I would never get used to the way Billie sometimes knew what I was saying even when I wasn’t saying it.

“Try to understand their point of view,” she went on. “In one letter he talks about coming home and it sounds like they’re planning to be together. It helps me to think one day we’ll be back there on the coast on a warm breezy day, all our troubles and this stupid war behind us.”

She shuffled the letters to find a certain passage. “He talks a lot about the war. I wish that dude Hank could hear some of this. Or your dad.”

“Uh, not a great idea,” I said.

“Ssshh… he says Now I see it’s quicksand. Everyone here has lost faith in the war but we keep fighting and hoping someone will throw us a rope and pull us out before we’re sucked all the way down.… See, that’s what I’m saying—your friend Hank, he has no idea, talking about fighting for freedom and all that.… Your letters are the only peace I have, Cole says, my oasis in this desert of a jungle where nothing grows but elephant grass and rice, land mines and booby traps, and rot and lies. This war is fueled on lies, he says. The World will never even know all the lies and insanity.”

She was talking with the letter in one hand, both hands fluttering around, rising and falling and circling and turning in the air, so that she occasionally had to stop and relocate where she’d been reading.

“Oh my god, this is intense. Oh my god, listen to this.… Last week we stopped in a little village to drop off some food and maybe pick up some intel. Supposedly a friendly village, all women and children except one shriveled old man. A few of us were in a shack where our medic was stitching up a cut by this old man’s eye. I happen to notice a loose floorboard, and the old man gets real nervous. I lift the board and see a stash of rifles and now the old man jumps up and starts yelling in Vietnamese. This kid from San Diego, this eighteen year old kid in-country for all of a week, who liked to drink beer and draw cartoon hot rods, he nuts up and opens fire, empties a whole clip on the old man, dude was face down in his own blood and the kid just kept shooting. The other villagers started running around shouting and the other soldiers started firing. They shot everyone in the place, twenty-seven enemy casualties, down to the last screaming baby.

“Wow… like My Lai,” I said.

“So heavy,” she said and sat down on the edge of the bed. “He sounds so sad and freaked out.… If they hadn’t caught up to me, maybe we’d be in Canada by now, together.… Oh no, listen to this, Archer.… One of those cops up in Shelter Cove told me it was Mike who turned me in. And, wouldn’t you know it, that pig Timmons showed up at the courthouse all the way up in Eureka just to make sure they got me to sign on for this shit. I should’ve gone to prison when I had the chance. I’ll never come back whole from this place, even if I don’t get shot or blown up.”

“I’ve heard of this,” I said. “They give you a choice—go to prison or join the army. Serves him right, I say.”

“But your dad! Turning the guy in like that? Not cool, man.” She shook her head in disgust.

The defensive side of the gin started talking. “Hey, my father told the truth.”

“How convenient. For him.”

“What was he supposed to do, just let my mother run away with some coward?”

“They were in love!”

“Why do girls act like the word love gives them a free pass for anything?”

“Why don’t boys understand love is the only thing worth fighting for?”

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved