The Blues & Billie Armstrong 21

PUZZLING NEWS

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

“Why do girls act like the word love gives them a free pass for anything?”

“Why don’t boys understand love is the only thing worth fighting for?”

Along with the letters, we discovered some other items in the bottom of the hatbox—more souvenirs of my mother’s secret history.

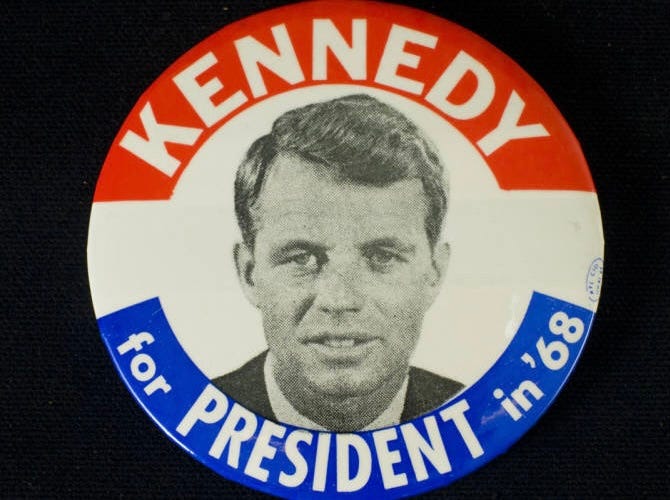

I sat on the messed-up bed and dumped it all onto the bedspread: a child’s dimestore kaleidoscope; a tiny polished abalone shell; a motel key on a beaded chain with a green plastic tag embossed with the black silhouette of a squawking crow and the words, The Crow’s Nest, Shelter Cove, California; a Robert Kennedy for President pin-button; and a Polaroid photo of my mother smiling in the blue hat on a windy bluff overlooking the ocean.

We went through each object, Billie and I handling them one by one, wondering how each one might or might not be connected to the letters and J.R. Cole.

Toward the end of the day, knowing the parents would return soon, I put everything back into the bottom of the box, covered it up with the paper, and noticed the oddly folded, slightly crumpled newspaper happened to be a page from the Lupoyoma Call & Record. The date was Friday, July 18, 1969.

“Right before the moon,” I said, absentmindedly.

“Huh?” Billie said.

“The date on this paper,” I said. “Two days before the moon landing… you know, Neil Armstrong and all that… and just a couple months before she died.”

Billie closed her eyes. “I was on the roof of an apartment house in Akron that night, partying with some friends. Someone hooked together a bunch of extension cords and brought a TV out on the roof so we could get stoned and look at the sky and watch Cronkite and the astronauts at the same time. It was a beautiful crescent moon,” she said, one hand reaching upward dramatically as if she could see the memory.

“I was watching Cronkite that night too, but in Lupoyoma it was like eight o’clock, and it was still light outside and hot as hell inside the house. I remember, Neil Armstrong coming down the ladder and my mother and father were out on the front porch arguing. My mother came in and slammed the screen door, and she stalked across the living room crying during Armstrong’s famous little speech and she disappeared into the dayroom.”

“Do you think it means anything?” Billie said.

“The newspaper?” I gave her the what-do-I-know shrug. “I guess not.” I set the hat on the paper, closed the box and handed it to Billie, and she returned it to the shelf in the closet.

During the winter after my mother died, I would often avoid going home to an empty house by heading for The Weeping Willow after school.

If none of my friends were in the game room, I’d stop by the restaurant to visit my grandparents. Molly had a jigsaw puzzle in progress on a corner table in the restaurant. She’d work on it when business was slow, and when I came by she'd invite me to fit a piece or two. At first, she just had the edges of the puzzle, all straight and square and connected. In the middle, separate pieces or clusters of pieces drifted untethered to the larger reality. But slowly, over that cold rainy winter, it came together to match the picture on the puzzle box, a blue and dark painting of cobbled streets and leafy saplings in thin moonlight beside shadowy water.

Now, the picture I had to work from was in my mind—the memory of my mother in the blue-flowered sundress, lying so still, the pills and the vodka on the nightstand, the scratch-scratch on the hi-fi. But, did I have all the pieces? The blues records, the letters, that windblown Polaroid and the rest of the souvenirs in the hatbox. Rawson Road, Shelter Cove, Vietnam. And which pieces belonged on the edges of the picture, and which would form the center? And, of course, the sealed, pink lipstick envelope sitting in the pocket of my robe—where did that fit?

When my father and Darlene came home from work, I played the role of recovering patient and offered assurances that I could go to school the next day.

Darlene made chicken noodle soup and gave me Jello pudding which I ate in my room thinking about the blues and the rest, especially that last letter from J.R. Cole, the quicksand letter. I didn’t want to admit it, but I was disappointed my father had turned Cole in to the authorities—it seemed small and unfair. He had taught me not to be a tattletale.

But wasn’t Cole wrong to run from his duty, even if the war was stupid and wrong in the first place? And was Billie right that Hank Timmons wasn’t ready for what he was getting into? I wondered how he would hold up under the conditions Cole described. And how would I if it ever came to that?

My mother was in the wrong as well, and yes, I was judging her. How could she get involved with this stranger and run away like that, leaving me behind? (Although taking me along might have been worse.) Billie was wrong too, digging through my mother’s stuff like some Haight-Ashbury Nancy Drew. And maybe I was every bit as wrong as everyone else, prying into all of this while keeping my own secrets.

I couldn’t finish this puzzle of rights and wrongs yet, and I couldn’t connect it all to that rainy Wednesday, my mother on the rollaway bed, the scratch-scratch in my ears. In journalistic terms, I had a whole lot of who, what, when and where, but barely the beginning of why.

After nightfall I lay in bed, under the blue wave bedspread, going over my thoughts like worry beads, and I stared at the darkened window until the faint glow disappeared from under my door and the TV voices no longer drifted back from the living room. When my ears caught the throbbing hum of the house, I knew all but myself were asleep. I tried to induce my own escape by spinning my usual fantasies, but I had begun to see that I couldn’t grow up by wishes and imaginary afflictions. I could be slow on the uptake but I wasn’t completely oblivious.

Like it or not (and I wasn’t a fan), there seemed to be a decision at hand. I could call it a day so to speak, draw the line here and like a politician simply declare victory. That might be the sensible thing, after all. Don’t wallow in the past, move on young man, the wider world doesn’t care about your heart’s petty bruises. Or I could continue this needy quest to finish the puzzle, to understand my mother’s end, damn the consequences.

I got out of bed and pulled on my robe. I stepped carefully as my eyes adjusted to the dark, and I tapped lightly on the window. After a few seconds Billie came to the window and raised the bottom pane several inches, slowly, to avoid the noisy scrape of the wood.

“What do you want?” She was sleepy, irritated.

I slipped the envelope out of the pocket of my robe and handed it across the window sill.

“Don’t open it,” I said.

Billie lit a match and examined the envelope in the flickering light. “Oh my god, where did this come from?”

We stayed there at the window for what seemed a long time, whispering in the dark, our heads just inches apart like a confessional, and I told Billie the story—the rain, the scratch-scratch, the blue-flowered sundress, Sad Hours, even the vodka and the pills and wanting to burn the whole damn mess.

“And no one else knows you were there?” Billie said.

“After I left her and ran away like that, how could I tell them?”

“I don’t blame you, man. I might’ve done the same,” she said, but I didn’t believe her.“

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved