The Blues & Billie Armstrong 47

A SIZE 9 WORLD

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

Hank stood halfway up the passageway, wobbly on rubber legs, and this time he heard me and jerked his head around. He pivoted to face me and pulled his head back as if sizing up the unexpected. His face all a question and the yellow moon over his shoulder.

Late in the morning, it was Chief Timmons himself who kicked in the dayroom door with his big black boots, the wooden door jam cracking and splintering like a lightning-struck tree.

And it was me startled awake into instant panic, me tugging on my robe and running around to the front room where Laurette, Grandma Junia and my father all stood in shock while Darlene screamed over and over, “What is happening! Don’t you need a warrant! Mike, do something!”

Then, before we all followed Timmons and two other officers into the dayroom, it was Laurette who took me by the shoulders and delivered the news to me, as she had in the game room the day my mother died. “Hank is dead and Billie is missing,” she said. And once again I had to pretend to Laurette that I knew nothing, was not a witness.

I hadn’t actually been in the dayroom since Wednesday afternoon when I was listening to the blues records. That was more than four days ago but, crossing the threshold now, I struggled to believe it was only four days because something astounding had happened in there. Across the far wall, on both sides of the painted window, Billie had designed, created and assembled a display that was much more than a collage. I didn’t know the term “mixed-media” at the time and I’m sure no one else in the room did either, but that’s what it was.

There were clippings cut from the San Francisco Sentinel, the San Francisco Chronicle, LIFE Magazine, and even the Lupoyoma Call & Record—a grim assortment of headlines, pics and passages tacked and taped and pasted to the walls, angled and jumbled and sometimes overlapping. King, RFK, Nixon, Agnew, Woodstock, My Lai, Apollo 13, the breakup of the Beatles, Kent State, the Hard Hat Riots, the Student Strikes, Jackson State… like 1969 and 1970 both threw up on the wall, and all of it arranged in a shape that suggested an angry tornado.

Guardsmen Fire on Rock Throwers; Stanford Protests Close Campus; Mayor Praises Police… A grainy photo of a beer-bellied policeman waving a pistol and pressing a boot to the chest of a bloodied protester lying in the street… Students Boycott Classes Across U.S.; Cops and Marchers Clash… A large bright picture of three cops in riot gear on a campus lawn with little clouds of tear gas hanging low in the air…

… An article titled Tragedy in the Heartland, with all the type painted over in black swaths like censorship, except for selected quotes… I feel like going some place and sitting down and vomiting and crying… I don’t feel that I have a future, except the possibility of getting killed or seeing my friends getting killed… We can’t look up to these hippies and long hairs. We had to shoot, maybe it’ll make these people wake up… It’s just like an order to clean up a latrine; you do what you’re told to do…

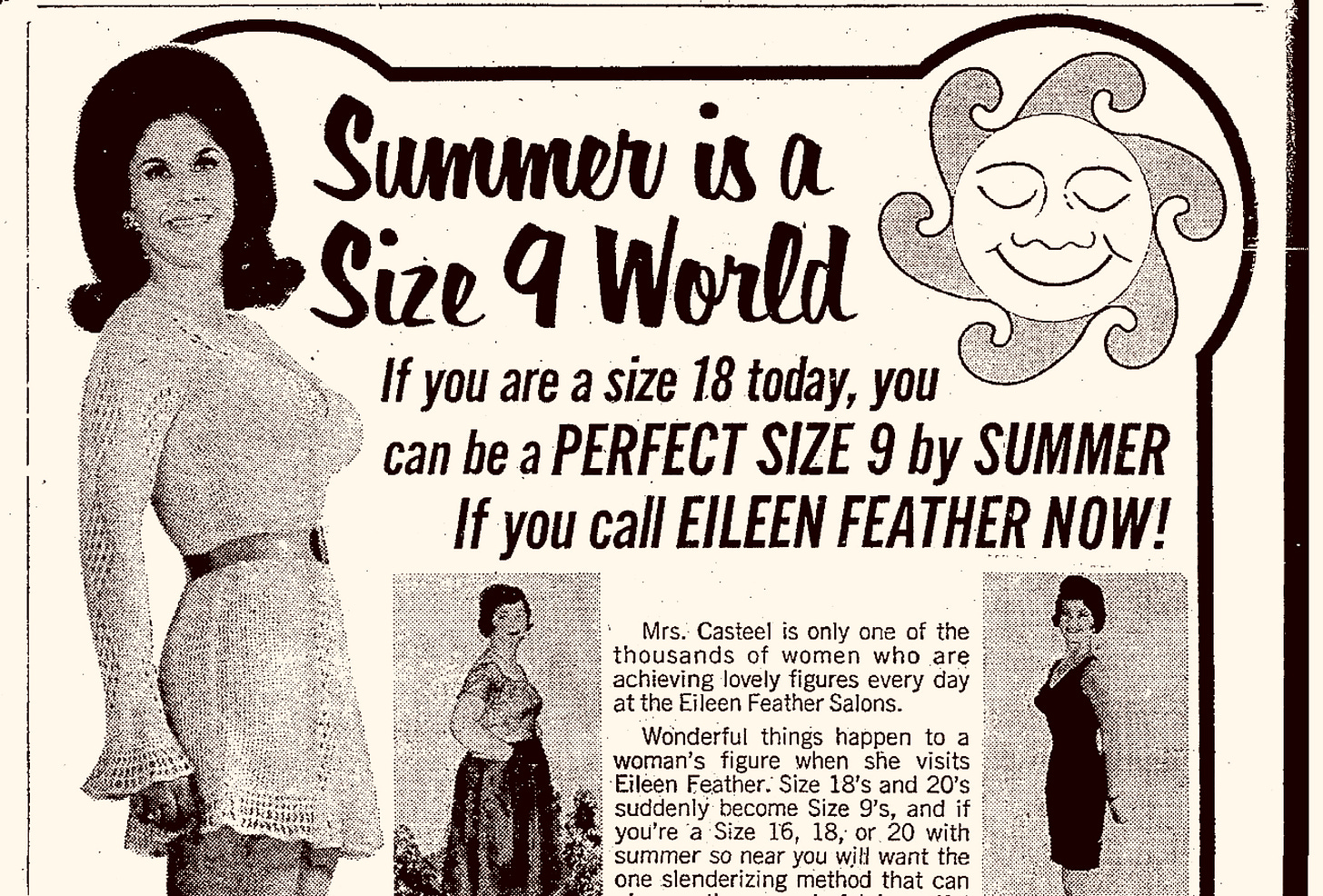

… A village on fire. A family’s home. Dead children piled up beside a dirt road. A headline says Before, Americans Always Brought us Candy and Medicine… right next to the ads for Chevrolets and cigarettes, Scotch whiskey, color televisions and life insurance… A busty woman in a crochet mini-dress, a tiny caption alongside her leg identified her as Eileen Feather, Leading Figure Authority. The huge boldface headline: SUMMER IS A SIZE 9 WORLD…

… And in the middle of all this, draped over the window, a man-size forty-eight-star American flag, hung upside down and splattered and dripping with blood red paint like someone got their head blown off in that room with a shotgun.

“Oh my god, Billie. Oh my god,” Darlene said.

Laurette gasped and wrapped an arm around me from behind in an anguished, protective hug, and I leaned back into her a bit in solidarity, commiseration, my mouth hanging open.

“I knew that girl was trouble from the get-go,” Grandma Junia huffed and shook her head side to side. “I said so, too.”

My father took a good long look around the room, arms crossed, gave it all a tight-lipped nod, turned and walked out without a word.

Timmons stood still, in a narrow-eyed staredown with the wall, especially the defiled flag. His jaw muscles clenched so tight I thought he might break teeth, one hand balled up in a fist, the other wrapped around the handle of his pistol.

My father came back grim-faced with drink in hand. “I warned her,” he said.

Grandma Junia said, “I gather this display is intended for us… some sort of political statement.” She pronounced display with withering disdain.

“It’s a work of art,” I said, but nobody listened.

“Frankly, it’s alarming,” said Grandma Junia.

“Can’t you see how upset she is?” Darlene said. “I think someone’s hurt her terribly.”

Chief Timmons said. “I want all of you out of this room. I don’t want anything touched. I want this room sealed, boarded up, off limits until I can get some detectives in here.”

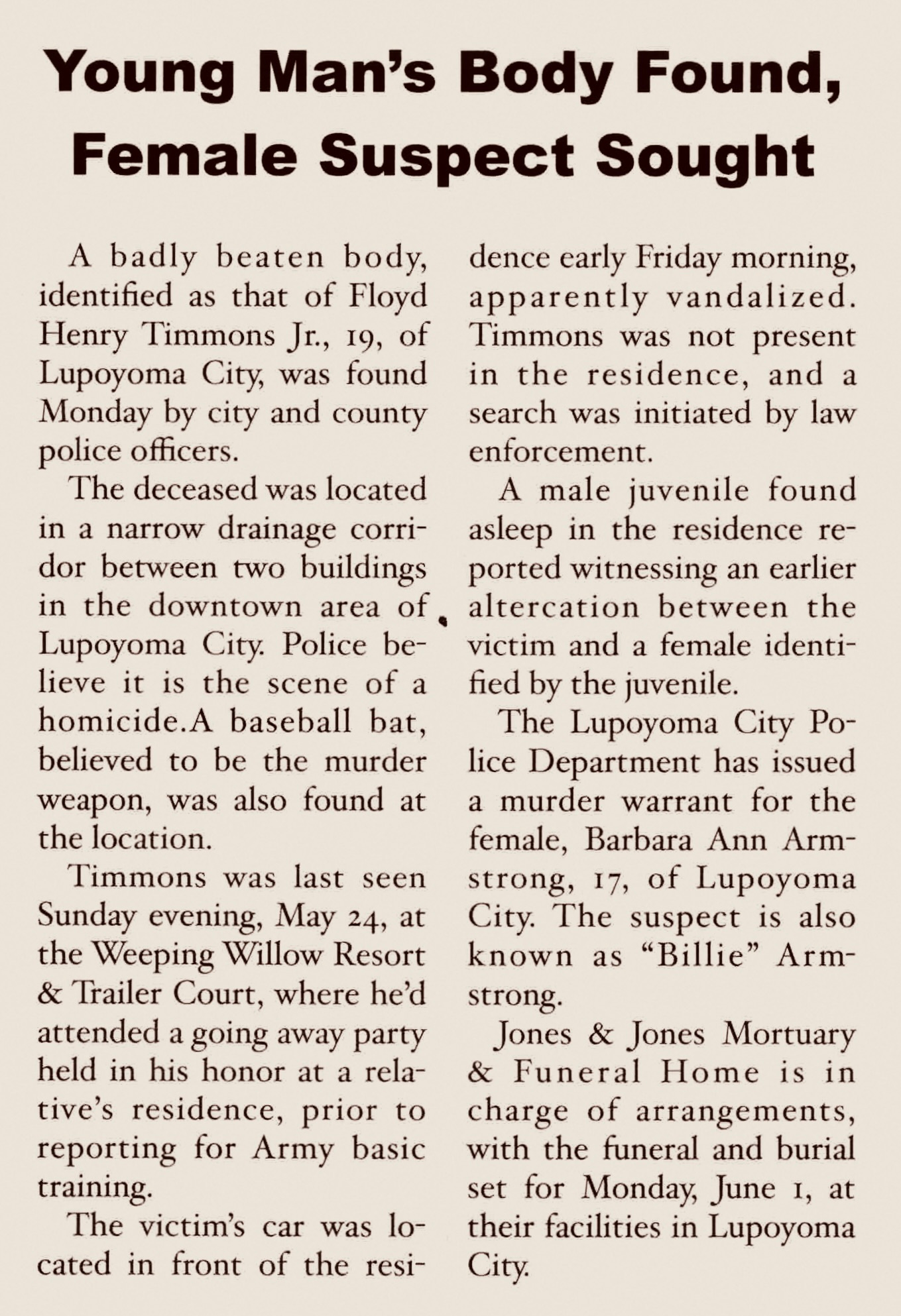

From the Lupoyoma Call & Record, May 27, 1970

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved