The Blues & Billie Armstrong 48

FUNERALS & OTHER ENDINGS

Previously in The Blues & Billie Armstrong…

Chief Timmons said. “I want all of you out of this room. I don’t want anything touched. I want this room sealed, boarded up, off limits until I can get some detectives in here.”

We all had to go to the funeral, for appearances if nothing else.

The too-familiar porch at Jones & Jones, my father in his gray suit, straining to show respect (and self-assured innocence) with as many solemn handshakes as he could distribute throughout the gathering. Grandma Junia flashing her superior frown in a swanky black outfit from a different era, pleated skirt and pillbox hat, a little half-veil in front of her eyes as if she’d been widowed again. And poor Darlene, all but dragged along, her red-eyed shame hidden behind dark dark sunglasses, desperately holding onto Laurette’s arm with every step.

“She’s got some nerve showing up here,” said Miss Lancaster, her imposing frame tented in black chiffon.

Half the town was there: Mr and Mrs Timmons, of course, the chief in full uniform glaring as we came into the chapel, as if we were all suspects. His broken wife crumpled in a folding chair, sniffling into a handkerchief.

But half the town was not there: Old Man Terwilliger (but not Alice); Leslie McGoogan and the rest of the Call & Record staff (minus Vic Pendergrass); Coach Fish and some other Paperboys (Timmy, but not Joey); a few former classmates (Tre Morgan but not Nate Henderson). Not surprisingly, Pop and Molly, Sonny the cook, Craiger and Eugene Robinson, all no-shows. Also Robyn Withrow, who had already been to one funeral that week and no doubt one was enough.

Meanwhile, the police had been searching everywhere for Billie Armstrong, now portrayed as a dangerous radical bent on political violence and wanted for the murder of a United States soldier.

The FBI was called in and set up checkpoints on all three of the roads leading out of Lupoyoma County. They swarmed the house, crime-taped the dayroom and snapped hundreds of pictures in there. They even picked through the Goodwill boxes, impervious to Grandma Junia’s strenuous objections.

They found the duffel bag in the Fairlane, dumped out the contents and took pictures of Billie’s eclectic wardrobe scattered on the lawn, including her underwear and the largely neglected bra. They even confiscated her sketchpad to pass on to some psychiatrist in San Francisco.

Sour-faced skinny-tie FBI agents lifted her paperback books by the corners of the covers as if the words inside might be contagious. Siddhartha, Mrs. Dalloway, On the Road, The Bell Jar, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Feminine Mystique. The Autobiography of Malcolm X — that one really got them scowling and pursing their lips.

They searched every inch of the car, but it was clean; she hadn’t had time to leave any evidence in there besides the duffel, and the car was still technically registered to Sonny, so they didn’t impound it. The keys were in the ignition and, days later, Sonny would show up and drive it away.

Other agents were busy checking out Billie’s relatives and childhood friends in Cleveland, and raiding her old crash-pad near the Kent State campus. They questioned Darlene, Laurette and Alice, and Molly and Sonny, too. I heard they gave Nate a real hard time, threatened to prosecute him for burning his draft card, but he knew his rights and there was not much he could tell them about Billie anyway.

And they questioned me, especially about the bat, branded as the murder weapon, and they took my fingerprints because they’d found three sets on the bat and were able to match Hank’s and Billie’s, but wanted to confirm the others were mine. I told them over and over I’d gone to bed and slept through the whole thing. “I barely knew her,” I said.

“Well, she was your sister,” the FBI guy said.

“Stepsister,” I said. “We really didn’t get along.”

When Laurette mentioned The Bus Stop, the detectives thought they finally had a lead. Rumors flew out the door and within hours everyone in Lupoyoma knew the traitor Frankie Watkins had helped Billie Armstrong escape, maybe even helped kill the Timmons boy. The agents all hurried out to Two Lakes and interrogated what was left of the Four Corners crew: Ben Parker, Old Sam, and shy Gilberto, but they all agreed Frankie had gone out of business and left town well before the dates in question. Apparently they never mentioned me. Or Garfunkel.

Disappointed, the FBI guys came back to our house and packed up. Billie had vanished without a trace and they were out of ideas for the time being. “She’s in the wind,” one of the agents said, all dramatic like a bad TV show.

Once all the cops were out of the house, my father and Darlene began to quarrel. She wanted him to search for Billie himself, maybe find her and talk her into turning herself in, get her a good lawyer and on and on. But my father said, “I told her I wouldn’t intervene on her behalf again. I warned her.”

“Michael, this is different,” Darlene pleaded.

“She’s caused enough trouble for this family already. I wash my hands of the whole affair.” He turned to me. “Now, I want you to clean up that room and take that garbage off the wall. I don’t want to see it again, is that understood?”

That night, I tore it all down, put all the paper clippings out back in the burn barrel, but I wasn’t sure what to do with that bloodied old flag, so I folded it up flat as I could and just barely managed to stuff it into my mother’s hatbox, still stashed in my closet.

Sunday, the day after Hank’s funeral, the Paperboys met the Odd Fellows for the third time that season—the much ballyhooed (and now dreaded) “rubber game.”

Once again it came down to the final inning, the final at-bat. The Paperboys were losing five-four and down to our last out against the fearsome Craiger Robinson. Timmy Bilderback worked a walk, and I somehow managed a grounder to left field that literally disappeared in the unmowed grass and was ruled a double. Dead ball. Time out. Timmy stood at third base and I stood at second, the potential—if highly unlikely—tying and winning runs.

Craiger’s brother Eugene jogged out from his position at shortstop and found the ball. He picked it up and started back in. Craiger ran out to meet him halfway, took the ball and gave his brother a don’t-worry-I-got-this pat on the shoulder. He walked back to the mound, pawed at the dirt with his cleats, stared in at the catcher. Like a good shortstop, Eugene held up two fingers and reminded his teammates, “Two down, two down.”

Timmy took a long lead off the bag at third, lowered into a half-squat and began dancing side to side, arms stretched out and hands shaking like some mad crab boogeyman. Even I was annoyed at the distraction.

Vic the umpire picked up his chest protector, pulled the mask down over his face and waved for the next batter, Joey Quarterman, AKA Joey Two Hits. We can still win this game, I thought. A clean base hit would score Timmy from third and give me a chance to race home with the winning run.

Joey dug in and took his stance. Vic hollered, “Play ball!” and lowered into his crouch behind the catcher. Craiger toed the rubber and began his windup. I took a short lead toward third, my heart drumming a syncopated six-eight rhythm.

Like a ghost, fat Eugene Robinson suddenly appeared beside me, pulled the ball out of his mitt and tagged me on the hip. “You’re out!” he yelled, and he held the ball up high and white for all to see. “You’re out! You’re out!” he kept saying, and he did a little dance, jumping round and round in the blonde infield dirt. The old hidden ball trick.

Craiger turned and showed me his empty glove. And a thin, satisfied smile.

Over the following week, Robyn and I met twice to study.

And on Friday the entire eighth grade class at Lupoyoma Junior High School sat in the cafeteria and took the Constitution Test. Then we all went home to worry.

But a week after that, on Friday June 12, we stood in line, heard our names (even Timmy Bilderback) and walked across the stage to receive our diplomas from the chairman of the school board, the ubiquitous Doc Meaney.

I wore the gray suit that Billie had picked out for me at Frankie’s store, and afterwards I even struggled through three minutes of slow dancing with Robyn the horse artist of all people, while Nate Henderson and Mellow Day struggled through the chord changes of Color My World by Chicago.

And the day after that, I came home from work to find Darlene hoisting her suitcase and a couple of overstuffed cardboard boxes into the back seat of Laurette’s VW Bug.

Laurette said, “If your father asks, I’m taking Darlene to her cousin’s in San Francisco. Although I wouldn’t be surprised if he doesn’t ask.”

“I’m sorry it didn’t work out, Archer,” Darlene said. She gave me a quick peck on the cheek, eyes brimming.

The Volkswagen went up the street, and I went up the front stairs and into the house.

Billie Armstrong had crashed into my life like a psychedelic wrecking ball, and on the way out she left a jagged splintered hole.

But now it felt over and done, and I had that sense of calm after storm, ashes after fire.

It was now almost three weeks since the night she disappeared, the night of Hank’s death, and all that time my whole life seemed to hang in the balance along with hers.

If she was caught, I’d told myself, I would tell the truth, or some of the truth, at least the part that would help her, protect her, save her. That’s what I’d told myself to feel brave and not feel the fear of actually having to follow through. But she hadn’t been caught, might never be caught, and I might never have to choose what to tell or what not to tell.

“Whoever knowingly mutilates, defaces, physically defiles, burns, maintains on the floor or ground, or tramples upon any flag of the United States…

…shall be fined under this title or imprisoned for not more than one year, or both.” — 1968 Flag Protection Act (found unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court, 1990)

“The flag, when it is in such condition that it is no longer a fitting emblem for display, should be destroyed in a dignified way, preferably by burning.” — American Legion U.S. Flag Code

I dug the hatbox out of my closet, pulled out Trey Morgan’s forty-eight-star flag. In my mind, in my heart, it was no longer a fitting emblem of the ideals it was intended to represent. It was defiled in spirit by the actions of Hank Timmons, even before it was used to cover Billie Armstrong’s naked escape, and even before its last service as part of her artistic farewell to Lupoyoma and our “family.”

Now was the time to retire this flag in a dignified way, and I decided in that moment to add my mother’s blue-flowered sundress to the ceremony as well. I threw several lit matches into the burn barrel until the news clippings caught and the flames began to grow. I lowered the flag in slowly as the fire climbed its folds.

After I dropped the last corner, I took the dress out of the Jones & Jones Funeral Home plastic, and I held it up by the hanger, let it unfold to full length and took a long look. I looked at the pocket where I had found the lipstick envelope. That day, I’d been so overcome, so confused, I’d never even thought to check the other pocket.

I reached in and my fingers recognized the touch of old newsprint…

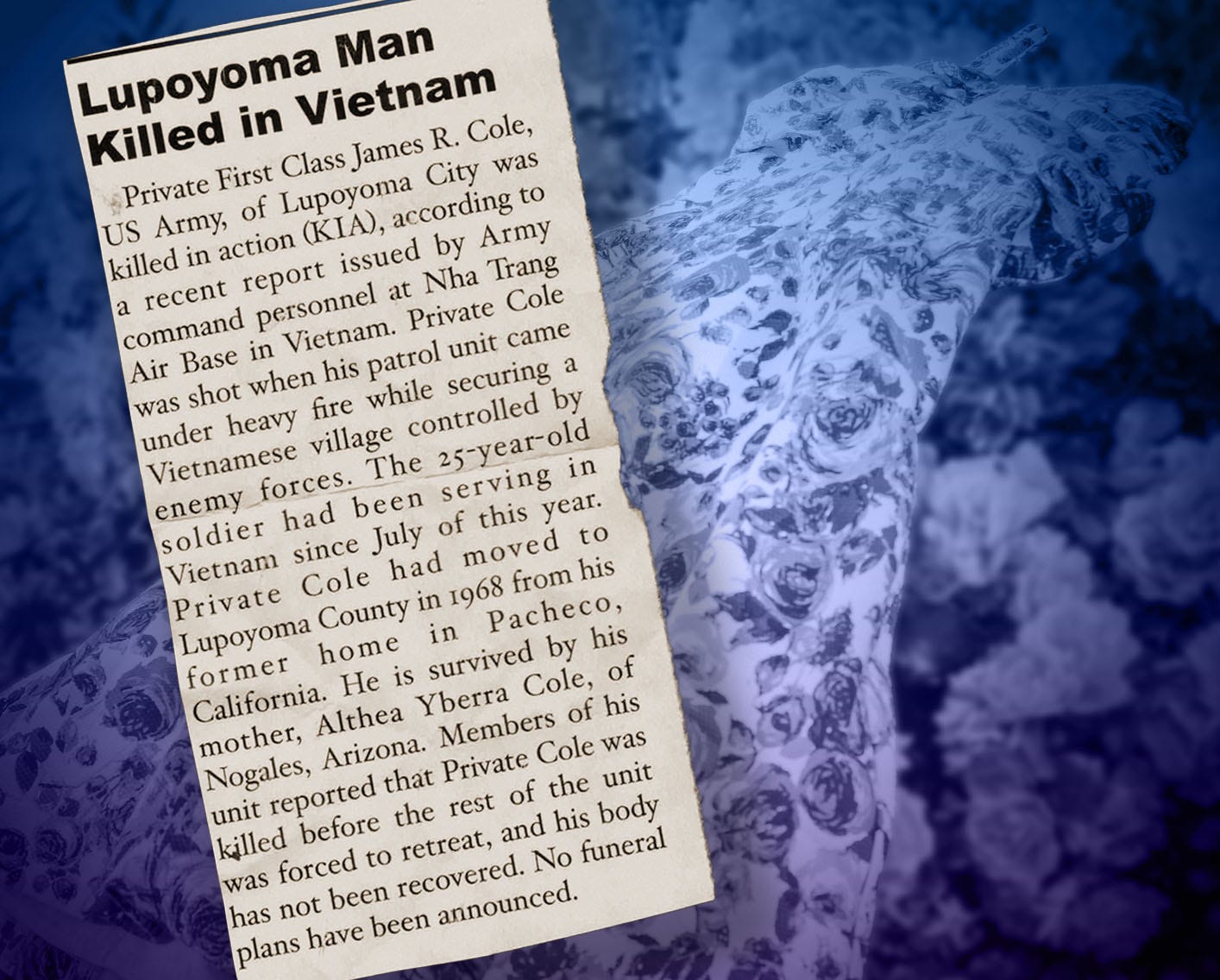

From the Lupoyoma Call & Record, July 18, 1969

The Blues & Billie Armstrong is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the fictional characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

© All Rights Reserved